Florida

| State of Florida | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

Nickname(s): The Sunshine State | |||||

Motto(s): In God We Trust (2006)[1][2] | |||||

State song(s): "Old Folks at Home (State Song), Florida (Where the Sawgrass Meets the Sky) (State Anthem)" | |||||

| |||||

| Official language | English[3] | ||||

| Spoken languages | Predominantly English and Spanish[4] | ||||

| Demonym | Floridian, Floridan | ||||

| Capital | Tallahassee | ||||

| Largest city | Jacksonville | ||||

| Largest metro | Greater Miami | ||||

| Area | Ranked 22nd | ||||

| • Total | 65,755[5] sq mi (170,304[5] km2) | ||||

| • Width | 361 miles (582 km) | ||||

| • Length | 447 miles (721 km) | ||||

| • % water | 17.9 | ||||

| • Latitude | 24° 27' N to 31° 00' N | ||||

| • Longitude | 80° 02' W to 87° 38' W | ||||

| Population | Ranked 3rd | ||||

| • Total | 21,312,211 (2018 est.)[6][7] | ||||

| • Density | 384.3/sq mi (121.0/km2) Ranked 8th | ||||

| • Median household income | $48,825[8] (41st) | ||||

| Elevation | |||||

| • Highest point | Britton Hill[9][10] 345 ft (105 m) | ||||

| • Mean | 100 ft (30 m) | ||||

| • Lowest point | Atlantic Ocean[9] Sea level | ||||

| Before statehood | Florida Territory | ||||

| Admission to Union | March 3, 1845 (27th) | ||||

| Governor | Rick Scott (R) | ||||

| Lieutenant Governor | Carlos López-Cantera (R) | ||||

| Legislature | Florida Legislature | ||||

| • Upper house | Senate | ||||

| • Lower house | House of Representatives | ||||

| U.S. Senators | Bill Nelson (D) Marco Rubio (R) | ||||

| U.S. House delegation | 16 Republicans 11 Democrats (list) | ||||

| Time zones | |||||

| • Peninsula and "Big Bend" region | EST: UTC −5/−4 | ||||

| • Panhandle west of the Apalachicola River | CST: UTC −6/−5 | ||||

| ISO 3166 | US-FL | ||||

| Abbreviations | FL, Fla. | ||||

| Website | myflorida.com | ||||

| Florida state symbols | |

|---|---|

The Flag of Florida | |

| Living insignia | |

| Amphibian | Barking tree frog |

| Bird | Northern mockingbird |

| Butterfly | Zebra longwing |

| Fish | Florida largemouth bass, Atlantic sailfish |

| Flower | Orange blossom |

| Mammal | Florida panther, manatee, bottlenose dolphin, Florida Cracker Horse[11] |

| Reptile | American alligator, Loggerhead turtle[11] |

| Tree | Sabal palmetto |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Orange juice |

| Food | Key lime pie, orange |

| Gemstone | Moonstone |

| Rock | Agatized coral |

| Shell | Horse conch |

| Soil | Myakka |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2004 | |

Lists of United States state symbols | |

Florida (/ˈflɒrɪdə/ (![]() listen); Spanish for "land of flowers") is the southernmost contiguous state in the United States. The state is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, and to the south by the Straits of Florida. Florida is the 22nd-most extensive (65,755 sq mi—170,304 km2), the 3rd-most populous (21,312,211 inhabitants),[12][7] and the 8th-most densely populated (384.3/sq mi—121.0/km2) of the U.S. states. Jacksonville is the most populous municipality in the state and the largest city by area in the contiguous United States. The Miami metropolitan area is Florida's most populous urban area. Tallahassee is the state's capital.

listen); Spanish for "land of flowers") is the southernmost contiguous state in the United States. The state is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, and to the south by the Straits of Florida. Florida is the 22nd-most extensive (65,755 sq mi—170,304 km2), the 3rd-most populous (21,312,211 inhabitants),[12][7] and the 8th-most densely populated (384.3/sq mi—121.0/km2) of the U.S. states. Jacksonville is the most populous municipality in the state and the largest city by area in the contiguous United States. The Miami metropolitan area is Florida's most populous urban area. Tallahassee is the state's capital.

About two-thirds of Florida occupies a peninsula between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. Florida has the longest coastline in the contiguous United States, approximately 1,350 miles (2,170 km), not including the contribution of the many barrier islands. It is the only state that borders both the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. Much of the state is at or near sea level and is characterized by sedimentary soil. Florida has the lowest high point of any U.S. state. The climate varies from subtropical in the north to tropical in the south.[13] The American alligator, American crocodile, American flamingo, Florida panther, bottlenose dolphin, and manatee can be found in Everglades National Park in the southern part of the state. Along with Hawaii, Florida is one of only two states that has a tropical climate, and is the only continental U.S. state with a tropical climate. It is also the only continental U.S. state with a coral reef called the Florida Reef.[14]

Since the first European contact was made in 1513 by Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León – who named it Florida, informally La Florida ([la floˈɾiða] "the land of flowers") upon landing there in the Easter season, Pascua Florida[15] – Florida was a challenge for the European colonial powers before it gained statehood in the United States in 1845. It was a principal location of the Seminole Wars against the Native Americans, and racial segregation after the American Civil War.

Today, Florida is distinctive for its large Cuban expatriate community and high population growth, as well as for its increasing environmental issues. The state's economy relies mainly on tourism, agriculture, and transportation, which developed in the late 19th century. Florida is also renowned for amusement parks, orange crops, winter vegetables, the Kennedy Space Center, and as a popular destination for retirees.

Florida's close proximity to the ocean influences many aspects of Florida culture and daily life. Florida is a reflection of influences and multiple inheritance; African, European, indigenous, and Latino heritages can be found in the architecture and cuisine. Florida has attracted many writers such as Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Ernest Hemingway and Tennessee Williams, and continues to attract celebrities and athletes. It is internationally known for golf, tennis, auto racing and water sports. Several beaches in Florida have turquoise and emerald-colored coastal waters.[16]

Contents

1 History

1.1 European arrival

1.2 Joining the United States; Indian removal

1.3 Slavery, war, and disenfranchisement

1.4 20th and 21st century growth

2 Geography

2.1 Climate

2.2 Fauna

2.3 Flora

2.4 Environmental issues

2.5 Geology

2.6 Regions

3 Demographics

3.1 Population

3.2 Settlements

3.3 Ancestry

3.4 Languages

3.5 Religion

4 Governance

4.1 Elections history

4.1.1 Elections of 2000 to present

4.2 Statutes

4.3 Law enforcement

5 Economy

5.1 Personal income

5.2 Real estate

5.3 Tourism

5.4 Agriculture and fishing

5.5 Industry

5.6 Mining

5.7 Government

6 Seaports

7 Health

8 Architecture

9 Media

10 Education

10.1 Primary and secondary education

10.2 Higher education

11 Transportation

11.1 Highways

11.2 Airports

11.3 Intercity rail

11.4 Public transit

12 Sports

13 Sister states

14 See also

15 References

16 Bibliography

17 External links

History

By the 16th century, the earliest time for which there is a historical record, major Native American groups included the Apalachee of the Florida Panhandle, the Timucua of northern and central Florida, the Ais of the central Atlantic coast, the Tocobaga of the Tampa Bay area, the Calusa of southwest Florida and the Tequesta of the southeastern coast.

European arrival

Map of Florida, likely based on the expeditions of Hernando de Soto (1539–1543).

Florida was the first region of the continental United States to be visited and settled by Europeans. The earliest known European explorers came with the Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de León. Ponce de León spotted and landed on the peninsula on April 2, 1513. He named the region Florida ("land of flowers").[17] The story that he was searching for the Fountain of Youth is mythical and only appeared long after his death.[18]

In May 1539, Conquistador Hernando de Soto skirted the coast of Florida, searching for a deep harbor to land. He described seeing a thick wall of red mangroves spread mile after mile, some reaching as high as 70 feet (21 m), with intertwined and elevated roots making landing difficult.[19] The Spanish introduced Christianity, cattle, horses, sheep, the Castilian language, and more to Florida.[20] Spain established several settlements in Florida, with varying degrees of success. In 1559, Don Tristán de Luna y Arellano established a settlement at present-day Pensacola, making it the first attempted settlement in Florida, but it was mostly abandoned by 1561.

The Castillo de San Marcos. Originally white with red corners, its design reflects the colors and shapes of the Cross of Burgundy and the subsequent Flag of Florida.

In 1565, the settlement of St. Augustine (San Agustín) was established under the leadership of admiral and governor Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, creating what would become one of the oldest, continuously-occupied European settlements in the continental U.S. and establishing the first generation of Floridanos and the Government of Florida.[21] Spain maintained strategic control over the region by converting the local tribes to Christianity. The marriage between Luisa de Abrego, a free black domestic servant from Seville, and Miguel Rodríguez, a white Segovian, occurred in 1565 in St. Augustine. It is the first recorded Christian marriage in the continental United States.[22]

Some Spanish married or had unions with Pensacola, Creek or African women, both slave and free, and their descendants created a mixed-race population of mestizos and mulattos. The Spanish encouraged slaves from the southern British colonies to come to Florida as a refuge, promising freedom in exchange for conversion to Catholicism. King Charles II of Spain issued a royal proclamation freeing all slaves who fled to Spanish Florida and accepted conversion and baptism. Most went to the area around St. Augustine, but escaped slaves also reached Pensacola. St. Augustine had mustered an all-black militia unit defending Spain as early as 1683.[23]

The geographical area of Florida diminished with the establishment of English settlements to the north and French claims to the west. The English attacked St. Augustine, burning the city and its cathedral to the ground several times. Spain built the Castillo de San Marcos in 1672 and Fort Matanzas in 1742 to defend Florida's capital city from attacks, and to maintain its strategic position in the defense of the Captaincy General of Cuba and the Spanish West Indies.

Grenadiers led by Bernardo de Gálvez at the Siege of Pensacola. Painting by Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau, 2015.

Florida attracted numerous Africans and African Americans from adjacent British colonies who sought freedom from slavery. In 1738, Governor Manuel de Montiano established Fort Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose near St. Augustine, a fortified town for escaped slaves to whom Montiano granted citizenship and freedom in return for their service in the Florida militia, and which became the first free black settlement legally sanctioned in North America.[24][25]

In 1763, Spain traded Florida to the Kingdom of Great Britain for control of Havana, Cuba, which had been captured by the British during the Seven Years' War. It was part of a large expansion of British territory following their victory in the Seven Years' War. A large portion of the Floridano population left, taking along most of the remaining indigenous population to Cuba.[26] The British soon constructed the King's Road connecting St. Augustine to Georgia. The road crossed the St. Johns River at a narrow point called Wacca Pilatka, or the British name "Cow Ford", ostensibly reflecting the fact that cattle were brought across the river there.[27][28][29]

East Florida and West Florida in British period (1763–1783)

The British divided and consolidated the Florida provinces (Las Floridas) into East Florida and West Florida, a division the Spanish government kept after the brief British period.[30] The British government gave land grants to officers and soldiers who had fought in the French and Indian War in order to encourage settlement. In order to induce settlers to move to Florida, reports of its natural wealth were published in England. A large number of British settlers who were described as being "energetic and of good character" moved to Florida, mostly coming from South Carolina, Georgia and England. There was also a group of settlers who came from the colony of Bermuda. This would be the first permanent English-speaking population in what is now Duval County, Baker County, St. Johns County and Nassau County. The British built good public roads and introduced the cultivation of sugar cane, indigo and fruits as well the export of lumber.[31][32]

As a result of these initiatives northeastern Florida prospered economically in a way it never did under Spanish administration. Furthermore, the British governors were directed to call general assemblies as soon as possible in order to make laws for the Floridas and in the meantime they were, with the advice of councils, to establish courts. This would be the first introduction of much of the English-derived legal system which Florida still has today including trial by jury, habeas corpus and county-based government.[31][32] Neither East Florida nor West Florida would send any representatives to Philadelphia to draft the Declaration of Independence. Florida would remain a Loyalist stronghold for the duration of the American Revolution.[33]

Spain regained both East and West Florida after Britain's defeat in the American Revolution and the subsequent Treaty of Versailles in 1783, and continued the provincial divisions until 1821.

Joining the United States; Indian removal

A Cracker cowboy, 19th century

Defense of Florida's northern border with the United States was minor during the second Spanish period. The region became a haven for escaped slaves and a base for Indian attacks against U.S. territories, and the U.S. pressed Spain for reform.

Americans of English descent and Americans of Scots-Irish descent began moving into northern Florida from the backwoods of Georgia and South Carolina. Though technically not allowed by the Spanish authorities and the Floridan government, they were never able to effectively police the border region and the backwoods settlers from the United States would continue to immigrate into Florida unchecked. These migrants, mixing with the already present British settlers who had remained in Florida since the British period, would be the progenitors of the population known as Florida Crackers.[34]

These American settlers established a permanent foothold in the area and ignored Spanish authorities. The British settlers who had remained also resented Spanish rule, leading to a rebellion in 1810 and the establishment for ninety days of the so-called Free and Independent Republic of West Florida on September 23. After meetings beginning in June, rebels overcame the garrison at Baton Rouge (now in Louisiana), and unfurled the flag of the new republic: a single white star on a blue field. This flag would later become known as the "Bonnie Blue Flag".

In 1810, parts of West Florida were annexed by proclamation of President James Madison, who claimed the region as part of the Louisiana Purchase. These parts were incorporated into the newly formed Territory of Orleans. The U.S. annexed the Mobile District of West Florida to the Mississippi Territory in 1812. Spain continued to dispute the area, though the United States gradually increased the area it occupied. In 1812, a group of settlers from Georgia, with de facto support from the U.S. federal government, attempted to overthrow the Floridan government in the province of East Florida. The settlers hoped to convince Floridans to join their cause and proclaim independence from Spain, but the settlers lost their tenuous support from the federal government and abandoned their cause by 1813.[35]

Seminoles based in East Florida began raiding Georgia settlements, and offering havens for runaway slaves. The United States Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory, including the 1817–1818 campaign against the Seminole Indians by Andrew Jackson that became known as the First Seminole War. The United States now effectively controlled East Florida. Control was necessary according to Secretary of State John Quincy Adams because Florida had become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them."[36]

Florida had become a burden to Spain, which could not afford to send settlers or garrisons. Madrid therefore decided to cede the territory to the United States through the Adams–Onís Treaty, which took effect in 1821.[37] President James Monroe was authorized on March 3, 1821 to take possession of East Florida and West Florida for the United States and provide for initial governance.[38]Andrew Jackson, on behalf of the U.S. federal government, served as a military commissioner with the powers of governor of the newly acquired territory for a brief period.[39] On March 30, 1822, the U.S. Congress merged East Florida and part of West Florida into the Florida Territory.[40]

A contemporaneous depiction of the New River Massacre in 1836

By the early 1800s, Indian removal was a significant issue throughout the southeastern U.S. and also in Florida. In 1830, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act and as settlement increased, pressure grew on the U.S. government to remove the Indians from Florida. Seminoles harbored runaway blacks, known as the Black Seminoles, and clashes between whites and Indians grew with the influx of new settlers. In 1832, the Treaty of Payne's Landing promised to the Seminoles lands west of the Mississippi River if they agreed to leave Florida. Many Seminole left at this time.

Some Seminoles remained, and the U.S. Army arrived in Florida, leading to the Second Seminole War (1835–1842). Following the war, approximately 3,000 Seminole and 800 Black Seminole were removed to Indian Territory. A few hundred Seminole remained in Florida in the Everglades.

On March 3, 1845, Florida became the 27th state to join the United States of America.[41] The state was admitted as a slave state and ceased to be a sanctuary for runaway slaves. Initially its population grew slowly.

As European settlers continued to encroach on Seminole lands, and the United States intervened to move the remaining Seminoles to the West. The Third Seminole War (1855–58) resulted in the forced removal of most of the remaining Seminoles, although hundreds of Seminole Indians remained in the Everglades.[42]

Slavery, war, and disenfranchisement

The Battle of Olustee during the American Civil War, 1864.

American settlers began to establish cotton plantations in north Florida, which required numerous laborers, which they supplied by buying slaves in the domestic market. By 1860, Florida had only 140,424 people, of whom 44% were enslaved. There were fewer than 1,000 free African Americans before the American Civil War.[43]

In January 10, 1861, nearly all delegates in the Florida Legislature approved an ordinance of secession,[44] declaring Florida to be "a sovereign and independent nation"—an apparent reassertion to the preamble in Florida's Constitution of 1838, in which Florida agreed with Congress to be a "Free and Independent State." Although not directly related to the issue of slavery, the ordinance declared Florida's secession from the Union, allowing it to become one of the founding members of the Confederate States, a looser union of states.

The confederal union received little help from Florida; the 15,000 men it offered were generally sent elsewhere. The largest engagements in the state were the Battle of Olustee, on February 20, 1864, and the Battle of Natural Bridge, on March 6, 1865. Both were Confederate victories.[45] The war ended in 1865.

Following the American Civil War, Florida's congressional representation was restored on June 25, 1868, albeit forcefully after Radical Reconstruction and the installation of unelected government officials under the final authority of federal military commanders. After the Reconstruction period ended in 1876, white Democrats regained power in the state legislature. In 1885 they created a new constitution, followed by statutes through 1889 that disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites.[46]

Until the mid-20th century, Florida was the least populous state in the southern United States. In 1900, its population was only 528,542, of whom nearly 44% were African American, the same proportion as before the Civil War.[47] The boll weevil devastated cotton crops.

Forty thousand blacks, roughly one-fifth of their 1900 population, left the state in the Great Migration. They left due to lynchings and racial violence, and for better opportunities.[48] Disfranchisement for most African Americans in the state persisted until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s gained federal legislation in 1965 to enforce protection of their constitutional suffrage.

20th and 21st century growth

Key West Historic District

Miami's Freedom Tower

Historically, Florida's economy has been based primarily upon agricultural products such as cattle, sugar cane, citrus fruits, tomatoes, and strawberries.

Economic prosperity in the 1920s stimulated tourism to Florida and related development of hotels and resort communities. Combined with its sudden elevation in profile was the Florida land boom of the 1920s, which brought a brief period of intense land development. Devastating hurricanes in 1926 and 1928, followed by the Great Depression, brought that period to a halt.

Florida's economy did not fully recover until the military buildup for World War II.

In 1939, Florida was described as "still very largely an empty State."[49] Subsequently, the growing availability of air conditioning, the climate, and a low cost of living made the state a haven. Migration from the Rust Belt and the Northeast sharply increased Florida's population after 1945. In the 1960s, many refugees from Cuba fleeing Fidel Castro's communist regime arrived in Miami at the Freedom Tower, where the federal government used the facility to process, document and provide medical and dental services for the newcomers. As a result, the Freedom Tower was also called the "Ellis Island of the South." [50] In recent decades, more migrants have come for the jobs in a developing economy.

With a population of more than 18 million according to the 2010 census, Florida is the most populous state in the southeastern United States and the third-most populous in the United States.

After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in September 2017, a large population of Puerto Ricans began moving to Florida to escape the widespread destruction. Hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans arrived in Florida after Maria dissipated, with nearly half of them arriving in Orlando and large populations also moving to Tampa, Fort Lauderdale, and West Palm Beach.[51]

Geography

A topographic map of Florida

Florida and its relation to Cuba and The Bahamas

Much of Florida is on a peninsula between the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic Ocean and the Straits of Florida. Spanning two time zones, it extends to the northwest into a panhandle, extending along the northern Gulf of Mexico. It is bordered on the north by Georgia and Alabama, and on the west, at the end of the panhandle, by Alabama. It is the only state that borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. Florida is west of The Bahamas and 90 miles (140 km) north of Cuba. Florida is one of the largest states east of the Mississippi River, and only Alaska and Michigan are larger in water area.

The water boundary is 3 nautical miles (3.5 mi; 5.6 km) offshore in the Atlantic Ocean[52] and 9 nautical miles (10 mi; 17 km) offshore in the Gulf of Mexico.[52]

At 345 feet (105 m) above mean sea level, Britton Hill is the highest point in Florida and the lowest highpoint of any U.S. state.[53] Much of the state south of Orlando lies at a lower elevation than northern Florida, and is fairly level. Much of the state is at or near sea level. However, some places such as Clearwater have promontories that rise 50 to 100 ft (15 to 30 m) above the water. Much of Central and North Florida, typically 25 mi (40 km) or more away from the coastline, have rolling hills with elevations ranging from 100 to 250 ft (30 to 76 m). The highest point in peninsular Florida (east and south of the Suwannee River), Sugarloaf Mountain, is a 312-foot (95 m) peak in Lake County.[54] On average, Florida is the flattest state in the United States.[55]

Climate

Köppen climate types of Florida

The climate of Florida is tempered somewhat by the fact that no part of the state is distant from the ocean. North of Lake Okeechobee, the prevalent climate is humid subtropical (Köppen: Cfa), while areas south of the lake (including the Florida Keys) have a true tropical climate (Köppen: Aw).[56] Mean high temperatures for late July are primarily in the low 90s Fahrenheit (32–34 °C). Mean low temperatures for early to mid January range from the low 40s Fahrenheit (4–7 °C) in north Florida to above 60 °F (16 °C) from Miami on southward. With an average daily temperature of 70.7 °F (21.5 °C), it is the warmest state in the U.S.[57]

In the summer, high temperatures in the state seldom exceed 100 °F (38 °C). Several record cold maxima have been in the 30s °F (−1 to 4 °C) and record lows have been in the 10s (−12 to −7 °C). These temperatures normally extend at most a few days at a time in the northern and central parts of Florida. South Florida, however, rarely encounters below freezing temperatures.[58] The hottest temperature ever recorded in Florida was 109 °F (43 °C), which was set on June 29, 1931 in Monticello. The coldest temperature was −2 °F (−19 °C), on February 13, 1899, just 25 miles (40 km) away, in Tallahassee.[59][60]

Due to its subtropical and tropical climate, Florida rarely receives measurable snowfall. However, on rare occasions, a combination of cold moisture and freezing temperatures can result in snowfall in the farthest northern regions. Frost, which is more common than snow, sometimes occurs in the panhandle.[citation needed] The USDA Plant hardiness zones for the state range from zone 8a (no colder than 10 °F or −12 °C) in the inland western panhandle to zone 11b (no colder than 45 °F or 7 °C) in the lower Florida Keys.[61]

| Average high and low temperatures for various Florida cities | ||||||||||||

°F | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Jacksonville[62] | 65/42 | 68/45 | 74/50 | 79/55 | 86/63 | 90/70 | 92/73 | 91/73 | 87/69 | 80/61 | 74/51 | 67/44 |

Miami[63] | 76/60 | 78/62 | 80/65 | 83/68 | 87/73 | 89/76 | 91/77 | 91/77 | 89/76 | 86/73 | 82/68 | 78/63 |

Orlando[64] | 71/49 | 74/52 | 78/56 | 83/60 | 88/66 | 91/72 | 92/74 | 92/74 | 90/73 | 85/66 | 78/59 | 73/52 |

Pensacola[65] | 61/43 | 64/46 | 70/51 | 76/58 | 84/66 | 89/72 | 90/74 | 90/74 | 87/70 | 80/60 | 70/50 | 63/45 |

Tallahassee[66] | 64/39 | 68/42 | 74/47 | 80/52 | 87/62 | 91/70 | 92/72 | 92/72 | 89/68 | 82/57 | 73/48 | 66/41 |

Tampa[67] | 70/51 | 73/54 | 77/58 | 81/62 | 88/69 | 90/74 | 90/75 | 91/76 | 89/74 | 85/67 | 78/60 | 72/54 |

°C | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Jacksonville | 18/6 | 20/7 | 23/10 | 26/13 | 30/17 | 32/21 | 33/23 | 33/23 | 31/21 | 27/16 | 23/11 | 19/7 |

Miami | 24/16 | 26/17 | 27/18 | 28/20 | 31/23 | 32/24 | 33/25 | 33/25 | 32/24 | 30/23 | 28/20 | 26/17 |

Orlando | 22/9 | 23/11 | 26/13 | 28/16 | 31/19 | 33/22 | 33/23 | 33/23 | 32/23 | 29/19 | 26/15 | 23/11 |

Pensacola | 16/6 | 18/8 | 21/11 | 24/14 | 29/19 | 32/22 | 32/23 | 32/23 | 31/21 | 27/16 | 21/10 | 17/7 |

Tallahassee | 18/4 | 20/6 | 23/8 | 27/11 | 31/17 | 33/21 | 33/22 | 33/22 | 32/20 | 28/14 | 23/9 | 19/5 |

Tampa | 21/11 | 23/12 | 25/14 | 27/17 | 31/21 | 32/23 | 32/24 | 33/24 | 32/23 | 29/19 | 26/16 | 22/12 |

Hurricane Andrew bearing down on Florida on August 23, 1992.

Hurricane Irma right before landfall in Florida on September 10, 2017. Hurricane Jose can be seen to the lower right.

Florida's nickname is the "Sunshine State", but severe weather is a common occurrence in the state. Central Florida is known as the lightning capital of the United States, as it experiences more lightning strikes than anywhere else in the country.[68] Florida has one of the highest average precipitation levels of any state,[69] in large part because afternoon thunderstorms are common in much of the state from late spring until early autumn. A narrow eastern part of the state including Orlando and Jacksonville receives between 2,400 and 2,800 hours of sunshine annually. The rest of the state, including Miami, receives between 2,800 and 3,200 hours annually.[70]

Florida leads the United States in tornadoes per area (when including waterspouts),[71] but they do not typically reach the intensity of those in the Midwest and Great Plains. Hail often accompanies the most severe thunderstorms.[citation needed]

Hurricanes pose a severe threat each year during the June 1 to November 30 hurricane season, particularly from August to October. Florida is the most hurricane-prone state, with subtropical or tropical water on a lengthy coastline. Of the category 4 or higher storms that have struck the United States, 83% have either hit Florida or Texas.[72]

From 1851 to 2006, Florida was struck by 114 hurricanes, 37 of them major—category 3 and above.[72] It is rare for a hurricane season to pass without any impact in the state by at least a tropical storm.[citation needed]

In 1992, Florida was the site of what was then the costliest weather disaster in U.S. history, Hurricane Andrew, which caused more than $25 billion in damages when it struck during August; it held that distinction until 2005, when Hurricane Katrina surpassed it, and it has since been surpassed by six other hurricanes. Andrew is currently the second costliest hurricane in Florida's history.

Hurricane Wilma, the third-most expensive hurricane in Florida's history, made landfall just south of Marco Island in October 2005. Wilma was responsible for about $21 billion in damages in Florida.[73][74]

Although many tropical storms would continue to affect the state after Wilma, it would be eleven years until the next hurricane, Hurricane Hermine struck the state, and twelve years until the next major hurricane, Hurricane Irma. After devastating multiple Caribbean islands as one of the most powerful Category 5 hurricanes ever recorded, Irma struck the Florida Keys as a Category 4 hurricane and made a second Florida landfall in Marco Island as a Category 3 hurricane.

While Irma's damage in Florida was far less than what was originally feared, it was still incredibly destructive, causing at least $50 billion in damages to Florida alone and around $66.8 billion in total, including damages to the many islands that were impacted.

This made it the costliest hurricane in Florida's history and the fifth costliest hurricane ever.

Fauna

An alligator in the Florida Everglades

Key deer in the lower Florida Keys

West Indian manatee

Florida panther native of South Florida

Florida is host to many types of wildlife including:

- Marine mammals: bottlenose dolphin, short-finned pilot whale, North Atlantic right whale, West Indian manatee

- Mammals: Florida panther, northern river otter, mink, eastern cottontail rabbit, marsh rabbit, raccoon, striped skunk, squirrel, white-tailed deer, Key deer, bobcats, red fox, gray fox, coyote, wild boar, Florida black bear, nine-banded armadillos, Virginia opossum

- Reptiles: eastern diamondback and pygmy rattlesnakes, gopher tortoise, green and leatherback sea turtles, and eastern indigo snake. In 2012, there were about one million American alligators and 1,500 crocodiles.[75]

- Birds: peregrine falcon,[76]bald eagle, northern caracara, snail kite, osprey, white and brown pelicans, sea gulls, whooping and sandhill cranes, roseate spoonbill, Florida scrub jay (state endemic), and others. One subspecies of wild turkey, Meleagris gallopavo, namely subspecies osceola, is found only in Florida.[77] The state is a wintering location for many species of eastern North American birds.

- As a result of climate change, there have been small numbers of several new species normally native to cooler areas to the north: snowy owls, snow buntings, harlequin ducks, and razorbills. These have been seen in the northern part of the state.[78]

- Invertebrates: carpenter ants, termites, American cockroach, Africanized bees, the Miami blue butterfly, and the grizzled mantis.

The only known calving area for the northern right whale is off the coasts of Florida and Georgia.[79]

The native bear population has risen from a historic low of 300 in the 1970s, to 3,000 in 2011.[80]

Since their accidental importation from South America into North America in the 1930s, the red imported fire ant population has increased its territorial range to include most of the southern United States, including Florida. They are more aggressive than most native ant species and have a painful sting.[81]

A number of non-native snakes and lizards have been released in the wild. In 2010 the state created a hunting season for Burmese and Indian pythons, African rock pythons, green anacondas, yellow anacondas, common boas, and Nile monitor lizards.[82]Green iguanas have also established a firm population in the southern part of the state.

There are about 500,000 feral pigs in Florida.[83]

Florida also has more than 500 nonnative animal species and 1,000 nonnative insects found throughout the state.[84] Some exotic species living in Florida include the Burmese python, green iguana, veiled chameleon, Argentine black and white tegu, peacock bass, lionfish, rhesus macaque, vervet monkey, Cuban tree frog, cane toad, monk parakeet, tui parakeet, and many more. Some of these nonnative species do not pose a threat to any native species, but some do threaten the native species of Florida by living in the state and eating them.[85]

Flora

The Sabal palmetto is one of twelve palm tree species that are native to Florida and is the official state tree.

There are about 3,000 different types of wildflowers in Florida. This is the third-most diverse state in the union, behind California and Texas, both larger states.[86]

On the east coast of the state, mangroves have normally dominated the coast from Cocoa Beach southward; salt marshes from St. Augustine northward. From St. Augustine south to Cocoa Beach, the coast fluctuates between the two, depending on the annual weather conditions.[78]

Environmental issues

The beaches of Key Biscayne in Miami

Florida is a low per capita energy user.[87] It is estimated that approximately 4% of energy in the state is generated through renewable resources.[88] Florida's energy production is 6% of the nation's total energy output, while total production of pollutants is lower, with figures of 6% for nitrogen oxide, 5% for carbon dioxide, and 4% for sulfur dioxide.[88]

All potable water resources have been controlled by the state government through five regional water authorities since 1972.[89]

Red tide has been an issue on the southwest coast of Florida, as well as other areas. While there has been a great deal of conjecture over the cause of the toxic algae bloom, there is no evidence that it is being caused by pollution or that there has been an increase in the duration or frequency of red tides.[90]

The Florida panther is close to extinction. A record 23 were killed in 2009, mainly by automobile collisions, leaving about 100 individuals in the wild. The Center for Biological Diversity and others have therefore called for a special protected area for the panther to be established.[91]Manatees are also dying at a rate higher than their reproduction.

Much of Florida has an elevation of less than 12 feet (3.7 m), including many populated areas. Therefore, it is susceptible to rising sea levels associated with global warming.[92]

The Atlantic beaches that are vital to the state's economy are being washed out to sea due to rising sea levels caused by climate change. The Miami beach area, close to the continental shelf, is running out of accessible offshore sand reserves.[93]

Geology

People swimming in Ginnie Springs near the town of High Springs, Florida

The Florida peninsula is a porous plateau of karst limestone sitting atop bedrock known as the Florida Platform.

The largest deposits of potash in the United States are found in Florida.[94]

Extended systems of underwater caves, sinkholes and springs are found throughout the state and supply most of the water used by residents. The limestone is topped with sandy soils deposited as ancient beaches over millions of years as global sea levels rose and fell. During the last glacial period, lower sea levels and a drier climate revealed a much wider peninsula, largely savanna.[95] The Everglades, an enormously wide, slow-flowing river encompasses the southern tip of the peninsula. Sinkhole damage claims on property in the state exceeded a total of $2 billion from 2006 through 2010.[96]

Florida is tied for last place as having the fewest earthquakes of any U.S. state.[97][98] Earthquakes are rare because Florida is not located near any tectonic plate boundaries.

Regions

The emerald-green waters of Destin on Florida's Emerald Coast

- Directional regions

- Central Florida

- North Florida

- Northwest Florida

- North Central Florida

- Northeast Florida

- South Florida

- Southwest Florida

- Coastal Regions

- Emerald Coast

- First Coast

- Forgotten Coast

- Gold Coast

- Surf Coast/Fun Coast/Halifax Area

- Nature Coast

- Space Coast

- Suncoast

- Treasure Coast

- Metropolitan regions

- Greater Miami Area/South Florida

- Tampa Bay Area

- Greater Orlando/Metro Orlando

- Greater Jacksonville/Metro Jacksonville

- Other regions

- Big Bend

- Florida Heartland

- Florida Keys

- Florida Panhandle

- Everglades

- Red Hills/Tallahassee Hills

- Ten Thousand Islands

- I-4 Corridor

Demographics

Florida's population density

Population

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1830 | 34,730 | — | |

| 1840 | 54,477 | 56.9% | |

| 1850 | 87,445 | 60.5% | |

| 1860 | 140,424 | 60.6% | |

| 1870 | 187,748 | 33.7% | |

| 1880 | 269,493 | 43.5% | |

| 1890 | 391,422 | 45.2% | |

| 1900 | 528,542 | 35.0% | |

| 1910 | 752,619 | 42.4% | |

| 1920 | 968,470 | 28.7% | |

| 1930 | 1,468,211 | 51.6% | |

| 1940 | 1,897,414 | 29.2% | |

| 1950 | 2,771,305 | 46.1% | |

| 1960 | 4,951,560 | 78.7% | |

| 1970 | 6,789,443 | 37.1% | |

| 1980 | 9,746,324 | 43.6% | |

| 1990 | 12,937,926 | 32.7% | |

| 2000 | 15,982,378 | 23.5% | |

| 2010 | 18,801,310 | 17.6% | |

| Est. 2017 | 20,984,400 | 11.6% | |

| Sources: 1910–2010[99] 2016 Estimate[100] | |||

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Florida was 20,271,272 on July 1, 2015, a 7.82% increase since the 2010 United States Census.[100] The population of Florida in the 2010 census was 18,801,310.[101] Florida was the seventh fastest-growing state in the U.S. in the 12-month period ending July 1, 2012.[102] In 2010, the center of population of Florida was located between Fort Meade and Frostproof. The center of population has moved less than 5 miles (8 km) to the east and approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) to the north between 1980 and 2010 and has been located in Polk County since the 1960 census.[103]

The population exceeded 19.7 million by December 2014, surpassing the population of the state of New York for the first time.[104]

Florida contains the highest percentage of people over 65 (17%).[105] There were 186,102 military retirees living in the state in 2008.[106]

About two-thirds of the population was born in another state, the second highest in the U.S.[107]

In 2010, undocumented immigrants constituted an estimated 5.7% of the population. This was the sixth highest percentage of any U.S. state.[108][109] There were an estimated 675,000 illegal immigrants in the state in 2010.[110]

A 2013 Gallup poll indicated that 47% of the residents agreed that Florida was the best state to live in. Results in other states ranged from a low of 18% to a high of 77%.[111]

Settlements

The largest metropolitan area in the state as well as the entire southeastern United States is the Miami metropolitan area, with about 6.06 million people. The Tampa Bay Area, with over 3.02 million people, is the second largest; the Orlando metropolitan area, with over 2.44 million people, is the third; and the Jacksonville metropolitan area, with over 1.47 million people, is fourth.

Florida has 22 Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) defined by the United States Office of Management and Budget (OMB). 43 of Florida's 67 counties are in a MSA.

The legal name in Florida for a city, town or village is "municipality". In Florida there is no legal difference between towns, villages and cities.[112]

In 2012, 75% of the population lived within 10 miles (16 km) of the coastline.[113]

Largest cities or towns in Florida Source:[114] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||||||

Jacksonville  Miami | 1 | Jacksonville | Duval | 892,062 |  Tampa  Orlando | ||||

| 2 | Miami | Miami-Dade | 463,347 | ||||||

| 3 | Tampa | Hillsborough | 385,430 | ||||||

| 4 | Orlando | Orange | 280,257 | ||||||

| 5 | St. Petersburg | Pinellas | 263,255 | ||||||

| 6 | Hialeah | Miami-Dade | 239,673 | ||||||

| 7 | Tallahassee | Leon | 191,049 | ||||||

| 8 | Port St. Lucie | St. Lucie | 189,344 | ||||||

| 9 | Cape Coral | Lee | 183,365 | ||||||

| 10 | Fort Lauderdale | Broward | 180,072 | ||||||

| Rank | Metropolitan Area | Population | Counties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach | 6,066,387 | Miami-Dade, Broward, Palm Beach |

| 2 | Tampa-St.Petersburg-Clearwater | 3,032,171 | Hillsborough, Pinellas, Pasco, Hernando |

| 3 | Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford | 2,441,257 | Orange, Seminole, Osceola, Lake |

| 4 | Jacksonville | 1,478,212 | Duval, St. Johns, Clay, Nassau, Baker |

| 5 | North Port-Sarasota-Bradenton | 788,457 | Sarasota, Manatee |

| 6 | Cape Coral-Fort Myers | 722,336 | Lee |

| 7 | Lakeland-Winter Haven | 666,149 | Polk |

| 8 | Deltona-Daytona Beach-Ormond Beach | 637,674 | Volusia, Flagler |

| 9 | Palm Bay-Melbourne-Titusville | 579,130 | Brevard |

| 10 | Pensacola-Ferry Pass-Brent | 485,684 | Escambia, Santa Rosa |

| Rank | Combined Statistical Areas | Population | Counties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Port St. Lucie | 6,723,472 | Miami-Dade, Broward, Palm Beach, St. Lucie, Martin, Indian River, Okeechobee |

| 2 | Orlando-Deltona-Daytona Beach | 3,202,927 | Orange, Volusia, Seminole, Osceola, Lake, Sumter, Flagler |

| 3 | Jacksonville-St. Mary's-Palatka | 1,603,497 | Duval, St. Johns, Clay, Nassau, Putnam, Camden, Baker |

| 4 | Cape Coral-Fort Myers-Naples | 1,087,472 | Lee, Collier |

| 5 | North Port-Sarasota-Bradenton | 1,002,722 | Sarasota, Manatee, Charlotte, DeSoto |

| 6 | Tallahassee-Bainbridge | 406,449 | Leon, Gadsden, Wakulla, Decatur, Jefferson |

| 7 | Gainesville-Lake City | 350,007 | Alachua, Columbia, Gilchrist |

Ancestry

Predominant ancestry in Florida in 2010

| Racial composition | 1970[115] | 1990[115] | 2000[116] | 2010[117] | 2017[118] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black or African American alone | 15.3% | 13.6% | 14.6% | 16.0% | 16.8% |

| Asian alone | 0.2% | 1.2% | 1.7% | 2.4% | 2.9% |

Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 6.6% | 12.2% | 16.8% | 22.5% | 24.9% |

| Native American alone | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.5% |

| Two or more races | – | – | 2.3% | 2.5% | 2.1% |

| White alone, not Hispanic or Latino | 77.9% | 73.2% | 65.4% | 57.9% | 54.9% |

| White alone | 84.2% | 83.1% | 78.0% | 75.0% | 77.6% |

Hispanic and Latinos of any race made up 22.5% of the population in 2010.[119] As of 2011, 57% of Florida's population younger than age 1 were minorities (meaning that they had at least one parent who was not non-Hispanic white).[120]

In 2010, 6.9% of the population (1,269,765) considered themselves to be of only American ancestry (regardless of race or ethnicity).[121][122] Many of these were of English or Scotch-Irish descent; however, their families have lived in the state for so long, that they choose to identify as having "American" ancestry or do not know their ancestry.[123][124][125][126][127][128] In the 1980 United States census the largest ancestry group reported in Florida was English with 2,232,514 Floridians claiming that they were of English or mostly English American ancestry.[129] Some of their ancestry went back to the original thirteen colonies.

As of 2010, those of (non-Hispanic white) European ancestry accounted for 57.9% of Florida's population. Out of the 57.9%, the largest groups were 12.0% German (2,212,391), 10.7% Irish (1,979,058), 8.8% English (1,629,832), 6.6% Italian (1,215,242), 2.8% Polish (511,229), and 2.7% French (504,641).[121][122]White Americans of all European backgrounds are present in all areas of the state. In 1970, non-Hispanic whites were nearly 80% of Florida's population.[130] Those of English and Irish ancestry are present in large numbers in all the urban/suburban areas across the state. Some native white Floridians, especially those who have descended from long-time Florida families, may refer to themselves as "Florida crackers"; others see the term as a derogatory one. Like whites in most other states of the southern U.S., they descend mainly from English and Scots-Irish settlers, as well as some other British American settlers.[131]

Cuban men playing dominoes in Miami's Little Havana. In 2010, Cubans made up 34.4% of Miami's population and 6.5% of Florida's.[132][133]

As of 2010, those of Hispanic or Latino ancestry accounted for 22.5% (4,223,806) of Florida's population. Out of the 22.5%, the largest groups were 6.5% (1,213,438) Cuban, 4.5% (847,550) Puerto Rican, 3.3% (629,718) Mexican, and 1.6% (300,414) Colombian.[133] Florida's Hispanic population includes large communities of Cuban Americans in Miami and Tampa, Puerto Ricans in Orlando and Tampa, and Mexican/Central American migrant workers. The Hispanic community continues to grow more affluent and mobile. As of 2011, 57.0% of Florida's children under the age of 1 belonged to minority groups.[134] Florida has a large and diverse Hispanic population, with Cubans and Puerto Ricans being the largest groups in the state. Nearly 80% of Cuban Americans live in Florida, especially South Florida where there is a long-standing and affluent Cuban community.[135] Florida has the second largest Puerto Rican population after New York, as well as the fastest-growing in the nation.[136] Puerto Ricans are more widespread throughout the state, though the heaviest concentrations are in the Orlando area of Central Florida.[citation needed]

As of 2010, those of African ancestry accounted for 16.0% of Florida's population, which includes African Americans. Out of the 16.0%, 4.0% (741,879) were West Indian or Afro-Caribbean American.[121][122][133] During the early 1900s, black people made up nearly half of the state's population.[137] In response to segregation, disfranchisement and agricultural depression, many African Americans migrated from Florida to northern cities in the Great Migration, in waves from 1910 to 1940, and again starting in the later 1940s. They moved for jobs, better education for their children and the chance to vote and participate in society. By 1960 the proportion of African Americans in the state had declined to 18%.[138] Conversely large numbers of northern whites moved to the state.[citation needed] Today, large concentrations of black residents can be found in northern and central Florida. Aside from blacks descended from African slaves brought to the southern U.S., there are also large numbers of blacks of West Indian, recent African, and Afro-Latino immigrant origins, especially in the Miami/South Florida area.

In 2016, Florida had the highest percentage of West Indians in the United States at 4.5%, with 2.3% (483,874) from Haitian ancestry, 1.5% (303,527) Jamaican, and 0.2% (31,966) Bahamian, with the other West Indian groups making up the rest.[139]

As of 2010, those of Asian ancestry accounted for 2.4% of Florida's population.[121][122]

Languages

In 1988 English was affirmed as the state's official language in the Florida Constitution. Spanish is also widely spoken, especially as immigration has continued from Latin America. Twenty percent of the population speak Spanish as their first language. Twenty-seven percent of Florida's population reports speaking a mother language other than English, and more than 200 first languages other than English are spoken at home in the state.[140][141]

The most common languages spoken in Florida as a first language in 2010 are:[140]

- 73% — English

- 20% — Spanish

- 2% — Haitian Creole

- Other languages comprise less than 1% spoken by the state's population

Religion

Florida is mostly Christian, although there is a large irreligious and relatively significant Jewish community. Protestants account for almost half of the population, but the Catholic Church is the largest single denomination in the state mainly due to its large Hispanic population and other groups like Haitians. Protestants are very diverse, although Baptists, Methodists, Pentecostals and nondenominational Protestants are the largest groups. There is also a sizable Jewish community in South Florida. This is the largest Jewish population in the southern U.S. and the third-largest in the U.S. behind those of New York and California.[143]

In 2010, the three largest denominations in Florida were the Catholic Church, the Southern Baptist Convention, and the United Methodist Church.[144]

The Pew Research Center survey in 2014 gave the following religious makeup of Florida:[145]

Governance

Old and New Florida State Capitol, Tallahassee, East view

The basic structure, duties, function, and operations of the government of the state of Florida are defined and established by the Florida Constitution, which establishes the basic law of the state and guarantees various rights and freedoms of the people. The state government consists of three separate branches: judicial, executive, and legislative. The legislature enacts bills, which, if signed by the governor, become law.

The Florida Legislature comprises the Florida Senate, which has 40 members, and the Florida House of Representatives, which has 120 members. The current Governor of Florida is Rick Scott.

The Florida Supreme Court consists of a Chief Justice and six Justices.

Florida has 67 counties. Some reference materials may show only 66 because Duval County is consolidated with the City of Jacksonville. There are 379 cities in Florida (out of 411) that report regularly to the Florida Department of Revenue, but there are other incorporated municipalities that do not. The state government's primary source of revenue is sales tax. Florida does not impose a personal income tax. The primary revenue source for cities and counties is property tax; unpaid taxes are subject to tax sales which are held (at the county level) in May and (due to the extensive use of online bidding sites) are highly popular.

There were 800 federal corruption convictions from 1988 to 2007, more than any other state.[146]

Elections history

| Registered Voters as of 2018 in Florida | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of Voters | Percentage | |||

Democratic | 4,815,369 | 37.28% | |||

Republican | 4,556,401 | 35.27% | |||

| Minor Parties | 72,166 | .56% | |||

No Party Affiliation | 3,474,166 | 26.89% | |||

| Total | 12,918,102 | 100% | |||

From 1952 to 1964, most voters were registered Democrats, but the state voted for the Republican presidential candidate in every election except for 1964. The following year, Congress passed and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, providing for oversight of state practices and enforcement of constitutional voting rights for African Americans and other minorities in order to prevent the discrimination and disenfranchisement that had excluded most of them for decades from the political process.

From the 1930s through much of the 1960s, Florida was essentially a one-party state dominated by white conservative Democrats, who together with other Democrats of the "Solid South", exercised considerable control in Congress. They have gained slightly less federal money from national programs than they have paid in taxes.[147] Since the 1970s, conservative white voters in the state have largely shifted from the Democratic to the Republican Party. Though the majority of registered voters in Florida are Democrats.[148] It continued to support Republican presidential candidates through 2004, except in 1976 and 1996, when the Democratic nominee was from "the South".

In the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections, Barack Obama carried the state as a northern Democrat, attracting high voter turnout especially among the young, Independents, and minority voters, of whom Hispanics comprise an increasingly large proportion. 2008 marked the first time since 1944, when Franklin D. Roosevelt carried the state for the fourth time, that Florida was carried by a Northern Democrat for president.

The first post-Reconstruction era Republican elected to Congress from Florida was William C. Cramer in 1954 from Pinellas County on the Gulf Coast,[149] where demographic changes were underway. In this period, African Americans were still disenfranchised by the state's constitution and discriminatory practices; in the 19th century they had made up most of the Republican Party. Cramer built a different Republican Party in Florida, attracting local white conservatives and transplants from northern and midwestern states. In 1966 Claude R. Kirk, Jr. was elected as the first post-Reconstruction Republican governor, in an upset election.[150] In 1968 Edward J. Gurney, also a white conservative, was elected as the state's first post-reconstruction Republican US Senator.[151] In 1970 Democrats took the governorship and the open US Senate seat, and maintained dominance for years.

Since the mid-20th century, Florida has been considered a bellwether, voting for 15 successful presidential candidates since 1952. During such period, it has voted for a losing candidate only twice.[152]

| Year | Republican | Democratic |

|---|---|---|

2016 | 49.02% 4,615,910 | 47.81% 4,501,455 |

2012 | 49.13% 4,163,447 | 50.01% 4,237,756 |

2008 | 48.22% 4,045,624 | 51.03% 4,282,074 |

2004 | 52.10% 3,964,522 | 47.09% 3,583,544 |

2000 | 48.85% 2,912,790 | 48.84% 2,912,253 |

1996 | 42.32% 2,244,536 | 48.02% 2,546,870 |

1992 | 40.89% 2,173,310 | 39.00% 2,072,698 |

1988 | 60.87% 2,618,885 | 38.51% 1,656,701 |

1984 | 65.32% 2,730,350 | 34.66% 1,448,816 |

1980 | 55.52% 2,046,951 | 38.50% 1,419,475 |

1976 | 46.64% 1,469,531 | 51.93% 1,636,000 |

1972 | 71.91% 1,857,759 | 27.80% 718,117 |

1968 | 40.53% 886,804 | 30.93% 676,794 |

1964 | 48.85% 905,941 | 51.15% 948,540 |

1960 | 51.51% 795,476 | 48.49% 748,700 |

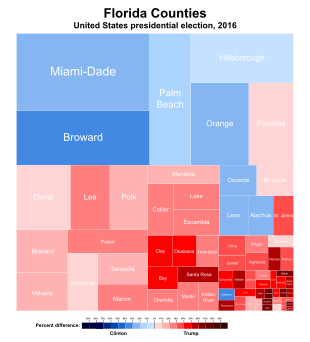

In 1998, Democratic voters dominated areas of the state with a high percentage of racial minorities and transplanted white liberals from the northeastern United States, known colloquially as "snowbirds".[153]South Florida and the Miami metropolitan area are dominated by both racial minorities and white liberals. Because of this, the area has consistently voted as one of the most Democratic areas of the state. The Daytona Beach area is similar demographically and the city of Orlando has a large Hispanic population, which has often favored Democrats. Republicans, made up mostly of white conservatives, have dominated throughout much of the rest of Florida, particularly in the more rural and suburban areas. This is characteristic of its voter base throughout the Deep South.[153]

The fast-growing I-4 corridor area, which runs through Central Florida and connects the cities of Daytona Beach, Orlando, and Tampa/St. Petersburg, has had a fairly even breakdown of Republican and Democratic voters. The area is often seen as a merging point of the conservative northern portion of the state and the liberal southern portion, making it the biggest swing area in the state. Since the late 20th century, the voting results in this area, containing 40% of Florida voters, has often determined who will win the state of Florida in presidential elections.[154]

The Democratic Party has maintained an edge in voter registration, both statewide and in 40 of the 67 counties, including Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties, the state's three most populous.[155]

Elections of 2000 to present

Treemap of the popular vote by county, 2016 presidential election.

In 2000, George W. Bush won the U.S. Presidential election by a margin of 271–266 in the Electoral College.[156] Of the 271 electoral votes for Bush, 25 were cast by electors from Florida.[157] The Florida results were contested and a recount was ordered by the court, with the results settled in a court decision.

Reapportionment following the 2010 United States Census gave the state two more seats in the House of Representatives.[158] The legislature's redistricting, announced in 2012, was quickly challenged in court, on the grounds that it had unfairly benefited Republican interests. In 2015, the Florida Supreme Court ruled on appeal that the congressional districts had to be redrawn because of the legislature's violation of the Fair District Amendments to the state constitution passed in 2010; it accepted a new map in early December 2015.

The political make-up of congressional and legislative districts has enabled Republicans to control the governorship and most statewide elective offices, and 17 of the state's 27 seats in the 2012 House of Representatives.[159] Florida has been listed as a swing state in Presidential elections since 1952, voting for the losing candidate only twice in that period of time.[160]

In the closely contested 2000 election, the state played a pivotal role.[156][157][161][162][163][164] Out of more than 5.8 million votes for the two main contenders Bush and Al Gore, around 500 votes separated the two candidates for the all-decisive Florida electoral votes that landed Bush the election win. Florida's felony disenfranchisement law is more severe than most European nations or other American states. A 2002 study in the American Sociological Review concluded that "if the state's 827,000 disenfranchised felons had voted at the same rate as other Floridians, Democratic candidate Al Gore would have won Florida—and the presidency—by more than 80,000 votes."[165]

In 2008, delegates of both the Republican Florida primary election and Democratic Florida primary election were stripped of half of their votes when the conventions met in August due to violation of both parties' national rules.

In the 2010 elections, Republicans solidified their dominance statewide, by winning the governor's mansion, and maintaining firm majorities in both houses of the state legislature. They won four previously Democratic-held seats to create a 19–6 Republican-majority delegation representing Florida in the federal House of Representatives.

In 2010, more than 63% of state voters approved the initiated Amendments 5 and 6 to the state constitution, to ensure more fairness in districting. These have become known as the Fair District Amendments. As a result of the 2010 United States Census, Florida gained two House of Representative seats in 2012.[158] The legislature issued revised congressional districts in 2012, which were immediately challenged in court by supporters of the above amendments.

The court ruled in 2014, after lengthy testimony, that at least two districts had to be redrawn because of gerrymandering. After this was appealed, in July 2015 the Florida Supreme Court ruled that lawmakers had followed an illegal and unconstitutional process overly influenced by party operatives, and ruled that at least eight districts had to be redrawn. On December 2, 2015, a 5–2 majority of the Court accepted a new map of congressional districts, some of which was drawn by challengers. Their ruling affirmed the map previously approved by Leon County Judge Terry Lewis, who had overseen the original trial. It particularly makes changes in South Florida. There are likely to be additional challenges to the map and districts.[166]

According to The Sentencing Project, the effect of Florida's felony disenfranchisement law is such that in 2014, "[m]ore than one in ten Floridians – and nearly one in four African-American Floridians – are [were] shut out of the polls because of felony convictions", although they had completed sentences and parole/probation requirements.[167]

Statutes

Florida Supreme Court Building

The state repealed mandatory auto inspection in 1981.[168]

In 1972, the state made personal injury protection auto insurance mandatory for drivers, becoming the second in the nation to enact a no-fault insurance law. The ease of receiving payments under this law is seen as precipitating a major increase in insurance fraud.[169] Auto insurance fraud was the highest in the nation in 2011, estimated at close to $1 billion.[170] Fraud is particularly centered in the Miami-Dade metropolitan and Tampa areas.[171][172][173]

Law enforcement

Florida was ranked the fifth-most dangerous state in 2009. Ranking was based on the record of serious felonies committed in 2008.[174] The state was the sixth highest scammed state in 2010. It ranked first in mortgage fraud in 2009.[175]

In 2009, 44% of highway fatalities involved alcohol.[176] Florida is one of seven states that prohibit the open carry of handguns. This law was passed in 1987.[177]

According to the Federal Trade Commission, Florida has the highest per capita rate of both reported fraud and other types of complaints including identity theft complaints.[178]

Economy

Launch of Space Shuttle Columbia from the Kennedy Space Center

Map of Florida showing average income by county.

The Brickell Financial District in Miami contains the largest concentration of international banks in the United States.[179][180]

In the twentieth century, tourism, industry, construction, international banking, biomedical and life sciences, healthcare research, simulation training, aerospace and defense, and commercial space travel have contributed to the state's economic development.[citation needed]

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Florida in 2016 was $926 billion.[181] Its GDP is the fourth largest economy in the United States.[182] In 2010, it became the fourth largest exporter of trade goods.[183] The major contributors to the state's gross output in 2007 were general services, financial services, trade, transportation and public utilities, manufacturing and construction respectively. In 2010–11, the state budget was $70.5 billion, having reached a high of $73.8 billion in 2006–07.[184] Chief Executive Magazine named Florida the third "Best State for Business" in 2011.[185]

The economy is driven almost entirely by its nineteen metropolitan areas. In 2004, they had a combined total of 95.7% of the state's domestic product.[186]

Personal income

In 2011, Florida's per capita personal income was $39,563, ranking 27th in the nation.[187] In February 2011, the state's unemployment rate was 11.5%.[188] Florida is one of seven states that do not impose a personal income tax.

Florida's constitution establishes a state minimum wage that is adjusted for inflation annually. As of January 1, 2017, Florida's minimum wage was $5.08 for tipped positions, and $8.10 for non-tipped positions, which was higher than the federal rate of $7.25.[189]

Florida has 4 cities in the top 25 cities in the U.S. with the most credit card debt.[190] The state also had the second-highest credit card delinquency rate, with 1.45% of cardholders in the state more than 90 days delinquent on one or more credit cards.[191]

There were 2.4 million Floridians living in poverty in 2008. 18.4% of children 18 and younger were living in poverty.[192] Miami is the sixth poorest big city in the United States.[193] In 2010, over 2.5 million Floridians were on food stamps, up from 1.2 million in 2007. To qualify, Floridians must make less than 133% of the federal poverty level, which would be under $29,000 for a family of four.[194]

Real estate

In the early 20th century, land speculators discovered Florida, and businessmen such as Henry Plant and Henry Flagler developed railroad systems, which led people to move in, drawn by the weather and local economies. From then on, tourism boomed, fueling a cycle of development that overwhelmed a great deal of farmland.

Due to the huge payouts by the insurance industry as a result of the hurricane claims of 2004, homeowners insurance has risen 40% to 60% and deductibles have risen.[73]

At the end of the third quarter in 2008, Florida had the highest mortgage delinquency rate in the U.S., with 7.8% of mortgages delinquent at least 60 days.[191] A 2009 list of national housing markets that were hard hit in the real estate crash included a disproportionate number in Florida.[195] The early 21st-century building boom left Florida with 300,000 vacant homes in 2009, according to state figures.[196] In 2009, the US Census Bureau estimated that Floridians spent an average 49.1% of personal income on housing-related costs, the third highest percentage in the U.S.[197]

In the third quarter of 2009, there were 278,189 delinquent loans, 80,327 foreclosures.[198] Sales of existing homes for February 2010 was 11,890, up 21% from the same month in 2009. Only two metropolitan areas showed a decrease in homes sold: Panama City and Brevard County. The average sales price for an existing house was $131,000, 7% decrease from the prior year.[199][dubious ]

Tourism

Walt Disney World Resort in Bay Lake, Florida near Orlando.

PortMiami is the world's largest cruise ship port.

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

If you can't find something to do in Florida, you're just boring...

— Guy Fieri, celebrity chef, 2017[200]

Tourism makes up one of the largest sectors of the state economy, with nearly 1.4 million people employed in the tourism industry in 2016 (a record for the state, surpassing the 1.2 million employment from 2015).[201][202] In 2015, Florida broke the 100-million visitor mark for the first time in state history by hosting a record 105 million visitors[202][203] and broke that record in 2016 with 112.8 million tourists; Florida has set tourism records for six consecutive years.[201]

Many beach towns are popular tourist destinations, particularly during winter and spring break, although activist David Hogg has called for a statewide boycott in 2018 unless state legislators pass substantive gun reform.[204] Twenty-three million tourists visited Florida beaches in 2000, spending $22 billion.[205] The public has a right to beach access under the public trust doctrine, but some areas have access effectively blocked by private owners for a long distance.[206]

Amusement parks, especially in the Greater Orlando area, make up a significant portion of tourism. The Walt Disney World Resort is the most visited vacation resort in the world with over 50 million annual visitors, consisting of four theme parks, 27 themed resort hotels, 9 non–Disney hotels, two water parks, four golf courses and other recreational venues.[207] Other major theme parks in the area include Universal Orlando Resort, SeaWorld Orlando and Busch Gardens Tampa.

Agriculture and fishing

Florida oranges

Agriculture is the second largest industry in the state. Citrus fruit, especially oranges, are a major part of the economy, and Florida produces the majority of citrus fruit grown in the United States. In 2006, 67% of all citrus, 74% of oranges, 58% of tangerines, and 54% of grapefruit were grown in Florida. About 95% of commercial orange production in the state is destined for processing (mostly as orange juice, the official state beverage).[208]

Citrus canker continues to be an issue of concern. From 1997 to 2013, the growing of citrus trees has declined 25%, from 600,000 acres (240,000 ha) to 450,000 acres (180,000 ha). Citrus greening disease is incurable. A study states that it has caused the loss of $4.5 billion between 2006 and 2012. As of 2014, it was the major agricultural concern.[209]

Other products include sugarcane, strawberries, tomatoes and celery.[210] The state is the largest producer of sweet corn and green beans for the U.S.[211]

The Everglades Agricultural Area is a major center for agriculture. The environmental impact of agriculture, especially water pollution, is a major issue in Florida today.

In 2009, fishing was a $6 billion industry, employing 60,000 jobs for sports and commercial purposes.[212]

Industry

Florida is the leading state for sales of powerboats. Boats sales totaled $1.96 billion in 2013.[213]

Mining

Phosphate mining, concentrated in the Bone Valley, is the state's third-largest industry. The state produces about 75% of the phosphate required by farmers in the United States and 25% of the world supply, with about 95% used for agriculture (90% for fertilizer and 5% for livestock feed supplements) and 5% used for other products.[214]

After the watershed events of Hurricane Andrew in 1992, the state of Florida began investing in economic development through the Office of Trade, Tourism, and Economic Development. Governor Jeb Bush realized that watershed events such as Andrew negatively impacted Florida's backbone industry of tourism severely. The office was directed to target Medical/Bio-Sciences among others. Three years later, The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) announced it had chosen Florida for its newest expansion. In 2003, TSRI announced plans to establish a major science center in Palm Beach, a 364,000 square feet (33,800 m2) facility on 100 acres (40 ha), which TSRI planned to occupy in 2006.[215]

Government

One of the Cape Canaveral launch sites during the launch of SpaceX CRS-13 in 2017

Since the development of the federal NASA Merritt Island launch sites on Cape Canaveral (most notably Kennedy Space Center) in 1962, Florida has developed a sizable aerospace industry.

Another major economic engine in Florida is the United States military. There are 24 military bases in the state, housing three Unified Combatant Commands; United States Central Command in Tampa, United States Southern Command in Doral, and United States Special Operations Command in Tampa. Some 109,390 U.S. military personnel stationed in Florida,[216] contributing, directly and indirectly, $52 billion a year to the state's economy.[217]

In 2009, there were 89,706 federal workers employed within the state.[218] Tens of thousands more employees work for contractors who have federal contracts, including those with the military.

In 2012, government of all levels was a top employer in all counties in the state, because this classification includes public school teachers and other school staff. School boards employ nearly 1 of every 30 workers in the state. The federal military was the top employer in three counties.[219]

Seaports

Port Tampa Bay is the largest port in Florida.

Florida has many seaports that serve container ships, tank ships, and cruise lines. Major ports in Florida include Port Tampa Bay in Tampa, Port Everglades in Fort Lauderdale, Port of Jacksonville in Jacksonville, PortMiami in Miami, Port Canaveral in Brevard County, Port Manatee in Manatee County, and Port of Palm Beach in Riviera Beach. The world's top three busiest cruise ports are found in Florida with PortMiami as the busiest and Port Canaveral and Port Everglades as the second and third busiest.[220] Port Tampa Bay meanwhile is the largest in the state, having the most tonnage. As of 2013, Port Tampa Bay ranks 16th in the United States by tonnage in domestic trade, 32nd in foreign trade, and 22nd in total trade. It is the largest, most diversified port in Florida, has an economic impact of more than $15.1 billion, and supports over 80,000 jobs.[221][222]

Health

The Miami Civic Center has the second-largest concentration of medical and research facilities in the United States.[223]

There were 2.7 million Medicaid patients in Florida in 2009. The governor has proposed adding $2.6 billion to care for the expected 300,000 additional patients in 2011.[224] The cost of caring for 2.3 million clients in 2010 was $18.8 billion.[225] This is nearly 30% of Florida's budget.[226] Medicaid paid for 60% of all births in Florida in 2009.[74] The state has a program for those not covered by Medicaid.

In 2013, Florida refused to participate in providing coverage for the uninsured under the Affordable Care Act, popularly called Obamacare. The Florida legislature also refused to accept additional Federal funding for Medicaid, although this would have helped its constituents at no cost to the state. As a result, Florida is second only to Texas in the percentage of its citizens without health insurance.[227]

Architecture

Miami Art Deco District, built during the 1920s–1930s.

Florida has the largest collection of Art Deco and Streamline Moderne buildings in both the United States and the entire world, most of which are located in the Miami metropolitan area, especially Miami Beach's Art Deco District, constructed as the city was becoming a resort destination.[228] A unique architectural design found only in Florida is the post-World War II Miami Modern, which can be seen in areas such as Miami's MiMo Historic District.

Being of early importance as a regional center of banking and finance, the architecture of Jacksonville displays a wide variety of styles and design principles. Many of state's earliest skyscrapers were constructed in Jacksonville, dating as far back as 1902,[229] and last holding a state height record from 1974 to 1981.[230] The city is endowed with one of the largest collections of Prairie School buildings outside of the Midwest.[231] Jacksonville is also noteworthy for its collection of Mid-Century modern architecture.[232]

Some sections of the state feature architectural styles including Spanish revival, Florida vernacular, and Mediterranean Revival.[233][234] A notable collection of these styles can be found in St. Augustine, the oldest continuously occupied European-established settlement within the borders of the United States.[235]

Media

Education

Primary and secondary education

With an educational system made up of public school districts and independent private institutions, Florida had 2,833,115 students enrolled in 4,269 public primary, secondary, and vocational schools in Florida's 67 regular or 7 special school districts as of 2018[update].[236]Miami-Dade County is the largest of Florida's 67 regular districts with over 350 thousand students and Jefferson is the smallest with less than one thousand students. Florida spent $8,920 for each student in 2016, and was 43rd in the nation in expenditures per student.[237] Florida’s cohort-based dropout rate has declined since 2011-12, with 0.9 percentage points fewer students dropping out prior to their scheduled graduation. The rate declined from 4.9 percent in 2011-12 to 4.0 percent in 2016-17.

Florida's primary and secondary school systems are administered by the Florida Department of Education. School districts are organized within county boundaries. Each school district has an elected Board of Education that sets policy, budget, goals, and approves expenditures. Management is the responsibility of a Superintendent of schools.

The Florida Department of Education is required by law to train educators in teaching English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL).[238]

Higher education

The State University System of Florida was founded in 1905, and is governed by the Florida Board of Governors. During the 2010 academic year, 312,216 students attended one of these twelve universities. The Florida College System comprises 28 public community and state colleges. In 2011–12, enrollment consisted of more than 875,000 students.[239] As of 2017 the University of Central Florida, with over 64,000 students, is the largest university by enrollment in the United States.[240]