Francisco de Miranda

| Francisco de Miranda | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Martín Tovar y Tovar | |

| Supreme Chief of Venezuela | |

In office 25 April 1812 – 26 June 1813 | |

| Preceded by | Francisco Espejo |

| Succeeded by | Simón Bolívar (As President of the Second Republic of Venezuela) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Sebastián Francisco de Miranda y Rodríguez de Espinoza (1750-03-28)28 March 1750 Caracas, Venezuela |

| Died | 14 July 1816(1816-07-14) (aged 66) Cádiz, Spain |

| Nationality | Venezuelan |

| Profession | Military |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | The Precursor The First Universal Venezuelan The Great Universal American |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1771–1812 |

| Rank | Generalissimo |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War French Revolution Siege of Melilla (1774) Venezuelan War of Independence |

Sebastián Francisco de Miranda y Rodríguez de Espinoza (Spanish pronunciation: [fɾanˈsisko ðe miˈɾanða]; March 28, 1750 – July 14, 1816), commonly known as Francisco de Miranda (Spanish pronunciation: [fɾanˈθisko ðe miˈɾanda]), was a Venezuelan military leader and revolutionary. Although his own plans for the independence of the Spanish American colonies failed, he is regarded as a forerunner of Simón Bolívar, who during the Spanish American wars of independence successfully liberated much of South America. He was known as "The First Universal Venezuelan" and "The Great Universal American". The director of the Center for Sephardic Studies in Caracas, José Chocrón Cohén, has suggested that Miranda could be related to the Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza, Isaac Miranda and Jacob Rodríguez Rivera. The surname Miranda appears twenty-eight times in "The Book of Blame" rescued by Anita Novinsky to study the surnames demanded by the Inquisition.[1] In the National Archive of Venezuela can be found the statute of the blood cleaning of the father of Francisco de Miranda (book nine).[2]

Miranda led a romantic and adventurous life in the general political and intellectual climate that emerged from the Age of Enlightenment that influenced all of the Atlantic Revolutions. He participated in three major historical and political movements of his time: the American Revolutionary War, the French Revolution and the Spanish American wars of independence. He described his experiences over this time in his journal, which reached to 63 bound volumes. An idealist, he developed a visionary plan to liberate and unify all of Spanish America, but his own military initiatives on behalf of an independent Spanish America ended in 1812. He was handed over to his enemies and four years later, died in a Spanish prison.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Hebrew-Jewish origin of Miranda

3 Education

3.1 Issues of ethnic lineage

4 Voyage to Spain (1771–1780)

4.1 In Madrid

4.2 Early campaigns

5 Missions in America (1781–1784)

5.1 American Revolution

5.2 The Antilles

5.3 Exile in the United States

6 In Europe (1785–1790)

6.1 Kingdom of Great Britain

6.2 Prussia

6.3 Russia

7 Miranda and the French Revolution (1791–1798)

8 Expeditions in South America (1804–1808)

8.1 Diplomatic negotiations, 1804–1805

8.2 Venezuela and the Caribbean, 1806

8.3 Project to attack Venezuela, 1808

9 The First Republic of Venezuela (1811–1812)

9.1 Return to Venezuela

9.2 Decay of the First Republic of Venezuela

9.2.1 Crisis of the Republic

9.2.2 Miranda's dictatorship

9.2.3 Defeat of the Republican army

9.3 The arrest of Miranda

10 Last years (1813–1816)

11 Miranda's ideals

11.1 Political beliefs

11.2 Freemasonry

12 Personal life

13 Legacy and honours

14 Gallery

15 References

16 Further reading

17 External links

Early life

Miranda was born in Caracas, Venezuela Province, in the Spanish colonial Viceroyalty of New Granada, and baptized on April 5, 1750. His father, Sebastian de Miranda Ravelo, was an immigrant from the Canary Islands who had become a successful and wealthy merchant, and his mother, Francisca Antonia Rodríguez de Espinoza, was a wealthy Venezuelan.[3]

Growing up, Miranda enjoyed a wealthy upbringing and attended the finest private schools. However, he was not necessarily a member of high society; his father faced some discrimination from rivals due to his Canarian roots.

Hebrew-Jewish origin of Miranda

In recent years, it has been argued that Francisco de Miranda may have been a descendant of marranos conversos. The surname Miranda appears twenty-eight times in "The Book of Blame" rescued by Anita Novinsky to study the surnames demanded by the Inquisition.[4] The surnames Rodríguez and Espinosa also deserve special attention.[5] In the National Archive of Caracas can be found the statute of the blood cleaning of the father of Francisco de Miranda (book nine).[2] The Jewish director of the Center for Sephardic Studies in Caracas, José Chocrón Cohen, has studied the unique and special connection that Miranda had with the Jewish world. The research made by Chocrón Cohén was presented at a presentation in the room of the Herrera Luque Foundation, located in Los Palos Grandes.[6] Natán Noé said that: "José Chocrón Cohén presented his paper on the philosemitism of the precursor hero of the independence of Venezuela, Francisco de Miranda, from a careful reading of his travel diary. The presentations culminated for 2015 and is already in preparation for the second season from February 2016".[6]

Throughout his career, it has been shown that Miranda had great philosemite traits. According to William Spence Robertson: "Beyond any doubt Leander's mother was Sarah Andrews, an uneducated woman reputed to be of Jewish extraction. Although Ricardo Becerra, a South American littérateur who composed a biography of Miranda, asserted that his hero was married to Miss Andrews, yet no certificate of such a marriage has ever been found."[7] Miranda was on the Jewish side and defended freedom of religion.[5] In his travel diary in the United States, his relationship with Ezra Stiles draws attention. Miranda learned Hebrew in the United States and showed admiration for the Jewish world. Newport was one of the most important destinations of Miranda in the United States, one of the most important Jewish settlements for the time. By then, Newport was more important than New York.[8] Also, Francisco de Miranda was the first foreign student to study in the United States.[9] According to the Maguén-Escudo magazine:[10]

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

Francisco de Miranda suffered a discrimination incident of the colonial Marrano world. His father had to verify the cleanliness of blood in a bureaucratic test. The event provoked the irritation of Miranda and it is necessary to recognize the latent continuation of that justifying impatience in the chain of legal claims that accompanied his life. It is worth remembering that his surname belongs to the famous town of Miranda, which is characterized as almost entirely marrano. Although this was not the personal case, such a condition could not be unknown in his time. The vindication, the courts, the demands accompanied the life of Miranda. His project of independence is almost a challenge that inherits the claim of the initial right.

— Fernando Yurman, Maguén-Escudo Jewish Magazine, number 154, pp. 41-52

In his diaries, you can also confirm that he was a friend of Jacob Rodriguez Rivera and described him as a Jew of character and honesty. During his travels, the Jewish quarter of the great European cities was his main destination. Behind the ambitious projects of Francisco de Miranda, may have been the capital of an important world network of Jewish merchants. Rodríguez Rivera, one of the contacts of Francisco de Miranda, was an important Jewish businessman who introduced the manufacture of wax or sperm oil in the United States. In addition, it is interesting that in Madrid there was another Francisco de Miranda who was the most important businessman of his time. This Francisco de Miranda in Spain was a crypto-Jew and, like his Venezuelan counterpart, was persecuted by the Inquisition.[11] This Francisco de Miranda in Madrid was the most important promoter of the Jewish religion in the area and negotiated the breadth of the political and economic rights of the community. José Chocrón Cohen wrote that:[5]

In the year 1709, barely forty-one years before the birth of the illustrious hero in question, a Jewish community was residing in Madrid, one of whose leaders was called Francisco de Miranda (maybe a collateral relative in ascending line of the Caracas hero?)

— José Chocrón Cohen

While it is difficult to prove that Miranda practiced the Jewish religion, his surnames are related to the Hebrew community that was expelled from Spain at the end of the 15th century. In fact, a Miranda family of Jewish religion came to the Venezuelan coast, long before the birth of the Venezuelan hero.[12] However, the fact of being a descendant of Jews does not imply that one is. Many residents of Venezuela were marranos. Chocrón Cohén indicates that, since 1810, Francisco de Miranda ordered to erase important records of his life and work. This process systematically eliminated numerous files. The destruction of the compromising archives for its fame could have also implied the destruction of the registries and files about its Jewish origin. Miranda took advantage of his public office to clear his name.[5] About the persecution against Francisco de Miranda, Fernando Yurman says:

On the other hand, the frequent accusations against Miranda as a "heretic," even though they should not be dissociated from the attack on free thought that his enlightened mood proposed, also refers to the remote appeals that were plotted against the Jewish community. The Jewish religious illustration and rationalism had a political affinity. This articulation is reinforced by the frequent appearance of Jewish scenes and scenes recorded by Miranda's biography, his visits and comments to the synagogue, the meeting and dialogue with Moisés Mendelsohn, the great Jewish philosopher and father of the Enlightenment, on libertarian themes of the time, his knowledge of the letter of the Jews supplied by Prince Pedro Dolgoruky.

— Fernando Yurman, Maguén-Escudo Jewish Magazine, number 154, pp. 41-52

For Francisco de Miranda, it was very important to travel with his genealogical documentation. William Spence Robertson said that: "In that document the testator named Turnbull and Vansittart as his executors and made a list of his property. This inventory included the goods in his home in Grafton Street as well as the bronzes, mosaics, and paintings in the custody of his friends in Paris. It described his private archives that contained documents respecting his ancestry and travels, his correspondence with French generals and ministers, and his papers concerning negotiations with the English Government in regard to Spanish-American emancipation." Sarah Andrews, his wife, served as a housekeeper or maid.[7]

The Jewish origin of Francisco de Miranda could have been demonstrated by the profession of his ancestors. For the descendants of Jews, it was not easy to change their profession. Catholics and Jews, at that time, were engaged in different professions. More difficult than changing your fatherland and last name, was to change your profession. The occupation of Miranda's father (canvas store) was one of the subjects of criticism by the Catholic landowner families (mantuanos) in Venezuela. This would explain the discrimination to which the family of Francisco de Miranda was subjected; Miranda had to demonstrate the cleanliness of their blood. The Canary Islands were also an important Jewish settlement. Francisco de Miranda could have been a descendant of these communities that fled from other regions of Spain. It is curious that many of Francisco de Miranda's Jewish friends around the world carried the same surnames as the genealogical tree of the Venezuelan hero. Often, Miranda noted in his diaries the percentage of Jewish labor that participated in the construction of the great monuments of humanity.[5] José Chocrón Cohen says that:

In fact, on December 25, 1810, a few days after his return to Venezuela, the Cabildo of Valencia had already given orders to erase from his acts and chapter books any mention or reference that would compromise the virtues and reputation of Miranda.

— José Chocrón Cohen, La identidad secreta de Miranda

Education

Miranda's father, Sebastian, always strove to improve the situation of the family, and in addition to accumulating wealth and attaining important positions, he ensured his children a college education. Miranda was first tutored by Jesuits, Jorge Lindo and Juan Santaella, before entering the Academy of Santa Rosa.[3]

On January 10, 1762, Miranda began his studies at the Royal and Pontifical University of Caracas, where he studied Latin, the early grammar of Nebrija, and the Catechism of Ripalda for two years. Miranda completed this preliminary course in September 1764 and became an upperclassman. Between 1764 and 1766, Miranda continued his studies, studying the writings of Cicero and Virgil, grammar, history, religion, geography and arithmetic.[3]

In June 1767, Miranda received his baccalaureate degree in the Humanities.[3] It is unknown if Miranda received the title of Doctor, as the only evidence in favor of this title is his personal testimony stating he received it in 1767, at age 17.

Issues of ethnic lineage

Beginning in 1767, Miranda's studies were disrupted in part due to his father's rising prominence in Caracas society. In 1764, Sebastian de Miranda was appointed the captain of the local militia known as the Company of the White Canary Islanders by the governor, Jose de Solano y Bote. Sebastian de Miranda directed his regiment for five years, but his new title and societal position bothered the white aristocracy (the Mantuanos). In retaliation, a competing faction formed a militia of its own and two local aristocrats, Don Juan Nicolas de Ponte and Don Martin Tovar Blanco, filed a complaint against Sebastian de Miranda.

Sebastian de Miranda requested and was granted honorary military discharge to avoid further antagonizing the local elite, and spent many years attempting to clear the family name and establish the "purity" of his family line. The need to establish the "cleanliness" of the family bloodline was important to maintain a place in society in Caracas, as it was what allowed the family to attend university, to marry in the church, and to attain government positions.[3] In 1769, Sebastian produced a notarized genealogy to prove that his family had no African, Jewish or Muslim ancestors, according to the records in the National Archive of Venezuela. Miranda's father obtained a blood cleanliness certificate, which should not be confounded with the blood nobility certificate.[2]

In 1770, Sebastian won his family's rights through an official royal patent, signed by Charles III, which confirmed Sebastian's title and societal standing.[13] The court ruling, however, created an irreconcilable enmity with the aristocratic elite, who never forgot the conflict nor forgave the challenge, which inevitably influenced subsequent decisions by Miranda.[3]

Voyage to Spain (1771–1780)

After the court victory of his father, Miranda decided to pursue a new life in Spain, and, on January 25, 1771, Miranda left Caracas from the port of La Guaira for Cadiz, Spain, on a Swedish frigate, the Prince Frederick.[3] Miranda landed at the Port of Cadiz on March 1, 1771, where he stayed for two weeks with a distant relative, Jose D'Anino,[3] before leaving for Madrid.[13]

In Madrid

On March 28, 1771, Miranda travelled to Madrid and took an interest in the libraries, architecture, and art that he found there.[3] In Madrid, Miranda pursued his education, especially modern languages, as they would allow him to travel throughout Europe.[3] He also sought to expand his knowledge of mathematics, history, and political science, as he aimed to serve the Spanish Crown as a military officer.[13] During this time, he also pursued genealogical research of his family name to establish his ties to Europe and Christianity, which was especially important to him after his father's struggles to legitimize their family line in Caracas.[13]

It was in Madrid that Miranda began to build his personal library, which he added to as he traveled, collecting books, manuscripts and letters.[13]

In January 1773, Miranda's father transferred 85,000 reales vellon (silver coins), to help his son obtain the position of captain in the Princess's Regiment.[3]

Early campaigns

During his first year as a captain, Miranda traveled with his regiment mainly in North Africa and the southern Spanish province of Andalusia. In December 1774, Spain declared War with Morocco, and Miranda experienced his first combat during the conflict.[3]

While Miranda was assigned to guard the stations of an unwanted colonial presence in North Africa, he began to draw connections to the similar colonial presence in Spanish South America. His first military feat took place during the siege of Melilla, held from December 9, 1774, to March 19, 1775, in which the Spanish forces managed to repel the Sultan of Morocco Mohammed ben Abdallah.[3] However, despite the actions taken and danger faced, Miranda did not get an award or promotion and was assigned to the garrison of Cadiz.[13]

Despite Miranda's success in the military, he faced many disciplinary complaints, ranging from complaints that he spent too much time reading, to financial discrepancies, to the most serious disciplinary charges of violence and abuse of authority.[3] One of Miranda's well-known enemies was Colonel Don Juan Manuel de Cagigal, who charged Miranda with the loss of company funds and brutalities against soldiers in Miranda's regiment. The account of the dispute was sent to Inspector General O'Reilly and eventually reached King Charles III, who ordered Miranda to be transferred back to Cadiz.[13]

Missions in America (1781–1784)

Siege of Pensacola

American Revolution

Spain became involved in the American Revolutionary War in order to expand their territories in Louisiana and Florida, to force Britain to maintain multiple simultaneous war fronts, and to seek a recovery of Gibraltar. The Spanish captain general of Louisiana, Bernardo de Gálvez, in 1779 attacked the British at Baton Rouge and Natchez, freeing the Mississippi River basin of hostile forces that could threaten its capital, New Orleans.

Spanish forces had begun moving against the British, and Miranda was ordered to report to the Regiment of Aragon, which sailed from Cadiz in spring of 1780 under Victoriano de Navia's command. Miranda reported to his chief, General Juan Manuel Cagigal y Monserrat, in Havana, Cuba. From their headquarters in Cuba, de Cagigal and Miranda participated in the Siege of Fort Pensacola on May 9, 1781, and Miranda was awarded the temporary title of lieutenant colonel during this action. Miranda also contributed to the French success of a naval battle at the Chesapeake Bay when he helped the Count de Grasse raise needed funds and supplies.[13]

The Antilles

Miranda remained prominent while in Pensacola, and in August 1781, Cagigal secretly sent Miranda to Jamaica to arrange for the release of 900 prisoners, see to their immediate needs, and acquire English ships for the Spanish Navy. Miranda was also asked to perform espionage work while staying with his British hosts. Miranda managed to perform a successful reconnaissance mission and also negotiated an agreement dated November 18, 1781, that regulated the exchange of Spanish prisoners. However, Miranda also entered into a deal with a British merchant, Philip Allwood. Miranda agreed to use the ships he had secured from the British to transport Allwood's goods back to Spain to sell them. Upon his return, Miranda was charged with being a spy and smuggler of British goods.[3]

The order to send Miranda back to Spain pursuant to the judgment of February 5, 1782, of the Supreme Inquisition Council failed to be met due to various faults of form and substance in the administrative process that caused the order to be questioned and, in part, by Cagigal's unconditional support of Miranda.

Miranda participated in the Capture of The Bahamas and carried news of the island's fall to his superior Bernardo de Gálvez. Gálvez was angry that the Bahamas expedition had gone ahead without his permission, and he imprisoned Cajigal and had Miranda arrested. Miranda was later released, but this experience of Spanish officialdom may have been a factor in his subsequent conversion to the idea of independence for Spain's American colonies.[14] The efficiency demonstrated by Miranda in the Bahamas led Cagigal to recommend that Miranda be promoted to colonel under the command of the General Commander of the Spanish forces in Cuba, Bernardo de Gálvez, in the town of Guárico.

At that time, the Spaniards were preparing a joint action with the French to invade Jamaica, the last British stronghold in the Gulf of Mexico, and Guárico was the ideal place to plan these operations, being close to the island and providing easy access for troops and commanders. Miranda was seen as the right person to plan operations because he had a firsthand knowledge of the situation of the British in the area. However, a preemptive attack by the British and the difficulties of the French fleet forced peace between Britain and France, so the invasion did not materialize and Miranda remained in Guárico.

Exile in the United States

With the failure of the invasion of Jamaica, priorities for the Spanish authorities changed, and the process of the Inquisition against Miranda became greater. Eventually Miranda's problems with the Inquisition became complicated and he was sent to Havana to be arrested and sent to Spain. For various reasons these plans were thwarted, and, fearing the imminence of his arrest, Miranda decided to go to the United States.[15] With the support of Cagigal, he escaped the surveillance of the Governor of Havana, and, aided by American James Seagrove who arranged the trip, he fled to New Bern, where he landed on July 10, 1783. During his time in the United States, Miranda made a critical study of its military defenses, which demonstrated extensive knowledge of the development of American conflict and circumstances.

While there, Miranda prepared and fixed a correspondence technique, used for the rest of his journey: he would meet people through the gift or loan of books, and examine the culture and customs of the places through which he passed in a methodical way.[15] Passing through Charleston, Philadelphia, and Boston, he dealt with different characters in American society. In New York City he met the prominent and politically connected Livingston family. Apparently Miranda had a romantic relationship with Susan Livingston, daughter of Chancellor Livingston. Although Miranda wrote to her for years, he never saw her again after leaving New York.

During his time in the United States, Miranda met with many important people. He was personally acquainted with George Washington in Philadelphia. He also met General Henry Knox,[15]Thomas Paine, Alexander Hamilton,[15]Samuel Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. He also visited various institutions of the new nation that impressed him such as the Library of Newport and Princeton College, Rhode Island College and Cambridge College.

In Europe (1785–1790)

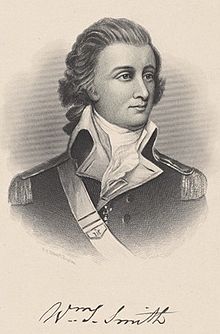

William Stephens Smith (1755-1816), one of the American friends of Miranda.

Kingdom of Great Britain

On December 15, 1784, Miranda left the port of Boston in the merchant frigate Neptuno for London and arrived in England on February 10, 1785. While in London, Miranda was discreetly watched by the Spanish, who were suspicious of him. The reports highlight that Miranda met with people suspected of conspiring against Spain and people considered among the eminent scholars of the time.

Prussia

The first secretary of the U.S. embassy, Colonel William Stephens Smith, whom Miranda knew from his stay in New York, came to England at around the same time.[15] Miranda and Smith decided to travel to Prussia[15] to attend military exercises prepared by King Frederick the Great of Prussia. Bernardo del Campo, Ambassador of Spain in the British capital since 1783, gave Miranda a letter of introduction to the Minister of Spain in Berlin, while James Penman, an English businessman whom Miranda had befriended in Charleston, was responsible for keeping his papers while he traveled.

However, the Spanish ambassador had secretly intrigued to have Miranda arrested when he reached Calais, France, where he could be handed over to Spain.[15] The plan fell apart because the Venezuelan and his friend went on 10 August 1785 to a Dutch port (Hellevoetsluis) instead.

Russia

Miranda then travelled throughout Europe, including present-day Belgium, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Poland, Greece and Italy, where he remained for over a year. After passing through Constantinople, he visited the court of Catherine the Great,[15] which had moved at that time from Moscow to Kiev (current Ukraine). In Hungary he stayed in the palace of Prince Nicholas Esterházy, who was sympathetic to his ideas, and wrote him a letter of recommendation to meet the musician Joseph Haydn.

Attempts to abduct Miranda by the diplomatic representatives of Spain failed as the Russian Ambassador in London, Semyon Vorontsov, declared on August 4, 1789, to the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Francis Osborne, 5th Duke of Leeds, that Miranda, although a Spanish subject, was a member of the Russian diplomatic mission in London. In Russia, he used the surname Meeroff and he left several children who later emigrated to the United States and Argentina.

Miranda made use of the Spanish–British diplomatic row known as the Nootka Crisis in February 1790 to present to some British Cabinet ministers his ideas about the independence of Spanish territories in South America.

Miranda and the French Revolution (1791–1798)

The Battle of Valmy

Starting in 1791, Miranda took an active part in the French Revolution[15] as marechal de camp. In Paris, he befriended the Girondists Jacques Pierre Brissot and Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve, and he briefly served as a general in the section of the French Revolutionary Army commanded by Charles François Dumouriez, fighting in the 1792 campaign of Valmy.

The Army of the North commanded by Miranda laid siege to Antwerp.[15] Miranda failed to take Maastricht in February 1793 and was first arrested in April 1793 on the orders of Antoine Quentin Fouquier-Tinville, Chief Prosecutor of the Revolution, and accused of conspiring against the republic with Charles François Dumouriez, the renegade general. Though indicted before the Revolutionary Tribunal – and under attack in Jean-Paul Marat's L'Ami du peuple – he and his lawyer Claude François Chauveau-Lagarde conducted his defence with such calm eloquence that he was declared innocent.[15]

However, Marat denounced Chauveau-Lagarde as a liberator of the guilty. Even so, the campaign of Marat and the rest of the Jacobins against him did not weaken. He was arrested again in July 1793 and incarcerated in La Force prison,[15] effectively one of the ante-chambers of death during the prevailing Reign of Terror. Appearing again before the tribunal, he accused the Committee of Public Safety of tyranny in disregarding his previous acquittal.

Miranda seems to have survived by a combination of good luck and political expediency: the revolutionary government simply could not agree on what to do with him. He remained in La Force even after the fall of Robespierre in July 1794, and was not finally released until January of the following year.[15] The art theorist Quatremère de Quincy was among those who campaigned for his release during this time.[16] Now convinced that the whole direction taken by the Revolution had been wrong, he started to conspire with the moderate royalists against the Directory, and was even named as the possible leader of a military coup. He was arrested and ordered out of the country, only to escape and go into hiding.

He reappeared after being given permission to remain in France, though that did not stop his involvement in yet another monarchist plot in September 1797. The police were ordered to arrest the "Peruvian general", as the said general submerged himself yet again in the underground. With no more illusions about France or the Revolution, he left for England in a Danish boat, arriving in Dover in January 1798.

Expeditions in South America (1804–1808)

Painting of Miranda by an unknown Incan author. 1806.

Diplomatic negotiations, 1804–1805

In 1804 with informal British help, Miranda presented a military plan to liberate the Captaincy General of Venezuela from Spanish rule.[15] At the time, Britain was at war with Spain, an ally of Napoleon. Home Riggs Popham was commissioned by prime minister Pitt in 1805 to study the plans proposed by Miranda to the British Government, Popham then persuaded the authorities that, as the Spanish Colonies were discontented, it would be more easy to promote a rising in Buenos Aires. Disappointed by this decision in November 1805, Miranda travelled to New York, where he rekindled his acquaintance with William S. Smith to organize an expedition to liberate Venezuela. Smith introduced him to merchant Samuel Ogden.[15]

Venezuela and the Caribbean, 1806

Miranda then went to Washington for private meetings with President Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison, who met with Miranda but did not involve themselves or their nation in his plans, which would have been a violation of the Neutrality Act of 1794.[15] In New York Miranda privately began organizing a filibustering expedition to liberate Venezuela. Along with Colonel Smith he raised private funds, procured weapons, and recruited soldiers of fortune. Among the 200 volunteers who served under him in this revolt were Smith's son William Steuben and David G. Burnet, who would later serve as interim president of the Republic of Texas after its secession from Mexico in 1836. Miranda hired a ship of 20 guns from Ogden, which he rebaptized Leander[15] in honor of his oldest son, and set sail to Venezuela on 2 February 1806.

Flag of Miranda used in 1806, during his expedition in Coro.

In Jacmel, Haiti, Miranda acquired two other ships, the Bee and the Bacchus, and their crews.[15] It was in Jacmel on March 12 that Miranda made and raised on the Leander, the first Venezuelan flag, which he had personally designed. On April 28, a botched landing attempt in Ocumare de la Costa resulted in two Spanish garda costas, Argos and Celoso, capturing the Bacchus and the Bee. Sixty men were imprisoned and put on trial in Puerto Cabello accused by piracy. Ten were sentenced to death, hanged and dismembered in quarters.[15] One of the victims was the printer Miles L. Hall, who for that reason has been considered as the first martyr of the printing press in Venezuela.

Miranda aboard of the Leander escaped, escorted by the packet ship HMS Lilly to the British islands of Grenada, Trinidad, and Barbados, where he met with Admiral Alexander Cochrane. As Spain was then at war with Britain, Cochrane and the governor of Trinidad Sir Thomas Hislop, 1st Baronet agreed to provide some support for a second attempt to invade Venezuela.[15]

The Leander left Port of Spain on 24 July, together with HMS Express, HMS Attentive, HMS Prevost, and HMS Lilly, carrying General Miranda and some 220 officers and men. General Miranda decided to land in La Vela de Coro and the squadron anchored there on 1 August. The next day the frigate HMS Bacchante joined them for three days. On 3 August, 60 Trinidadian volunteers under the Count de Rouveray, 60 men under Colonel Dowie, and 30 seamen and marines from HMS Lilly under Lieutenant Beddingfelt landed. This force cleared the beach of Spanish forces and captured a battery of four 9- and 12-pounder guns; the attackers had four men severely wounded, all from HMS Lilly. Shortly thereafter, boats from HMS Bacchante landed American volunteers and seamen and marines. The Spanish retreated, which enabled this force to capture two forts mounting 14 guns.[15]

General Miranda then marched on and captured Santa Ana de Coro, but found no support from the city residents.[15] However, on 8 August a Spanish force of almost 2000 men arrived. They captured a master of transport and 14 seamen who were getting water, unbeknownst to Lieutenant Donald Campbell. HMS Lilly landed 20 men on the morning of 10 August; this landing party killed a dozen Spaniards, but was able to rescue only one of the captive seamen. Colonel Downie and 50 men were sent, but the colonel judged the enemy force too strong and withdrew. When another 400 men came from Maracaibo, General Miranda realized that his force was too small to achieve anything further or to hold Coro for long. On August 13, Miranda ordered his force to set sail again. HMS Lilly and her squadron then carried him and his men safely to Aruba.[15][17]

In the aftermath of the failed expedition, Colonel Smith and Ogden were indicted by a federal grand jury in New York for piracy and violating the Neutrality Act of 1794. Put on trial Colonel Smith claimed his orders came from President Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison, who refused to appear in court. Both Colonel Smith and Ogden stood trial and were found not guilty.[15]

Project to attack Venezuela, 1808

Miranda spent the next year in Trinidad as host of governor Hyslop waiting for reinforcements that never came. On his return to London, he was met with better support for his plans from the British government after the failed invasions of Buenos Aires (1806–1807). In 1808 a large military force to attack Venezuela was assembled and placed under the command of Arthur Wellesley, but Napoleon's invasion of Spain suddenly transformed Spain into an ally of Britain, and the force instead went there to fight in the Peninsular War.

The First Republic of Venezuela (1811–1812)

Reception of Miranda in La Guaira, Johann Moritz Rugendas. A delegation from the Supreme Junta of Caracas, among them Bolívar, and a crowd of common people enthusiastically receive Miranda (19th century. Collection of the Fundación John Boulton, Caracas, Venezuela).

Return to Venezuela

Venezuela achieved de facto independence on Maundy Thursday April 19, 1810, when the Supreme Junta of Caracas was established and the colonial administrators deposed. The Junta sent a delegation to Great Britain to get British recognition and aid. This delegation, which included future Venezuelan notables Simón Bolívar and Andrés Bello, met with and persuaded Miranda to return to his native land. In 1811 a delegation from the Supreme Junta, among them Bolívar, and a crowd of common people enthusiastically received Miranda in La Guaira. In Caracas he agitated for the provisional government to declare independence from Spain under the rule of Joseph Bonaparte.

Miranda gathered around him a group of similarly minded individuals and helped establish an association, la Sociedad Patriotica, modeled on the political clubs of the French Revolution. By the end of the year, the Venezuelan provinces elected a congress to deal with the future of the country, and Miranda was chosen as the delegate from El Pao, Barcelona Province. On July 5, 1811, it formally declared Venezuelan independence and established a republic. The congress also adopted his tricolor as the Republic's flag.

Decay of the First Republic of Venezuela

Crisis of the Republic

5 de Julio de 1811, by Juan Lovera (1838). Francisco de Miranda (front right in the painting, 52nd in the legend below) was one of the politicians who signed the first Venezuelan Constitution.

The following year Miranda and the young Republic's fortunes turned. Republican forces failed to subdue areas of Venezuela (the provinces of Coro, Maracaibo and Guyana) that had remained royalist. In addition, Venezuela's loss of the Spanish market for its main export, cocoa, caused an economic crisis, which mostly hurt the middle and lower classes, who lost enthusiasm for the Republic. Finally a powerful earthquake and its aftershocks hit the country, which caused large numbers of deaths and serious damage to buildings, mostly in republican areas.

It did not help that it hit on March 26, 1812, as services for Maundy Thursday were beginning. The Caracas Junta had been established on a Maundy Thursday April 19, 1810 as well, so the earthquake fell on its second anniversary in the liturgical calendar. This was interpreted by many as a sign from Providence. It was explained by royalist authorities as divine punishment for the rebellion against the Spanish Crown.

The archbishop of Caracas, Narciso Coll y Prat, referred to the event as "the terrifying but well-deserved earthquake" that "confirms in our days the prophecies revealed by God to men about the ancient impious and proud cities: Babylon, Jerusalem and the Tower of Babel". Many, including those in the Republican army and the majority of the clergy, began to secretly plot against the Republic or outright defect. Other provinces refused to send reinforcements to Caracas Province. Worse still, whole provinces began to switch sides. On July 4, an uprising brought Barcelona over to the royalist side.

Miranda's dictatorship

Neighboring Cumaná, now cut off from the Republican center, refused to recognize Miranda's dictatorial powers and his appointment of a commandant general. By the middle of the month, many of the outlying areas of Cumaná Province had also defected to the royalists. With these circumstances a Spanish marine frigate captain, Domingo Monteverde, operating out of Coro, was able to turn a small force under his command into a large army, as people joined him on his advance towards Valencia, leaving Miranda in charge of only a small area of central Venezuela.[18] In these dire circumstances Miranda was given broad political powers by his government.

Defeat of the Republican army

Bolívar lost control of San Felipe Castle of Puerto Cabello along with its ammunition stores on 30 June 1812. Deciding that the situation was lost, Bolívar effectively abandoned his post and retreated to his estate in San Mateo. By mid-July Monteverde had taken Valencia and Miranda also saw the republican cause as lost. He started negotiations with royalists that finalized an armistice on July 25, 1812, signed in San Mateo. Then Colonel Bolívar and other revolutionary officers claimed his actions as treasonous.

The arrest of Miranda

Bolívar and others arrested Miranda and handed him over to the Spanish Royal Army in La Guaira port.[19] For his apparent services to the royalist cause, Monteverde granted Bolívar a passport, and Bolívar left for Curaçao on 27 August.[20] Miranda went to the port of La Guaira intending to leave on a British ship before the royalists arrived, although under the armistice there was an amnesty for political offenses. Bolívar claimed afterwards that he wanted to shoot Miranda as a traitor but was restrained by the others; Bolívar's reasoning was that, "if Miranda believed the Spaniards would observe the treaty, he should have remained to keep them to their word; if he did not, he was a traitor to have sacrificed his army to it."[21]

By handing over Miranda to the Spanish, Bolívar assured himself a passport from the Spanish authorities (passports which, nevertheless, had been guaranteed to all republicans who requested them by the terms of the armistice), which allowed him to leave Venezuela unmolested, and Miranda thought that the situation was hopeless.[22]

Last years (1813–1816)

Miranda never saw freedom again. His case was still being processed when he died in a prison cell at the Penal de las Cuatro Torres at the Arsenal de la Carraca, outside Cádiz, aged 66, on July 14, 1816. He was buried in a mass grave, making it impossible to identify his remains, so an empty tomb has been left for him in the National Pantheon of Venezuela.[23][24]

Miranda's ideals

Comparative maps of the envisioned nation of Colombia, according to Miranda (1798, left) and Bolívar (1826, right).

Political beliefs

Miranda has long been associated with the struggle of the Spanish colonies in Latin America for independence. He envisioned an independent empire consisting of all the territories that had been under Spanish and Portuguese rule, stretching from the Mississippi River to Cape Horn. This empire was to be under the leadership of a hereditary emperor called the "Inca", in honor of the great Inca Empire, and would have a bicameral legislature.[25] He conceived the name Colombia for this empire, after the explorer Christopher Columbus.[26]

Freemasonry

Similarly to some others in the history of American Independence (George Washington, José de San Martín, Bernardo O'Higgins and Simón Bolívar), Miranda was a Freemason. In London he founded the lodge "The Great American Reunion".[27]

Personal life

After fighting for Revolutionary France, Miranda finally made his home in London, where he had two children, Leandro (1803 – Paris, 1886) and Francisco (1806 – Cerinza, Colombia, 1831),[28][29] with his housekeeper, Sarah Andrews, whom he later married. He had a friendship with James Barry, the uncle of Margaret Bulkley, who was living as James Barry; Miranda helped to keep her secret so that she could become a doctor.[30] According to historian Linda de Pauw, "Miranda was an ardent feminist, named women as his literary executors, and published an impassioned plea for female education a year before Mary Wollstonecraft published her famous Vindication of the Rights of Women."[31]

Legacy and honours

- An oil painting by the Venezuelan artist Arturo Michelena, Miranda en la Carraca (1896), which portrays the hero in the Spanish jail where he died, has become a graphic symbol of Venezuelan history, and has immortalized the image of Miranda for generations of Venezuelans.

- The name of Miranda remains engraved on the Arc de Triomphe, which was built during the First Empire, and his portrait is in the Palace of Versailles. His statue is in the Square de l'Amérique-Latine in the 17th arrondissement.

- Miranda's name has been honoured several times, including in the name of the Venezuelan state, Miranda (created in 1889), a Venezuelan harbour, Puerto Miranda, a subway station and an important main avenue in Caracas, as well as a number of Venezuelan municipalities named "Miranda" or "Francisco de Miranda".

- Both Caracas airbase and a Caracas park are named after him.

- The Order of Francisco de Miranda was established in the 1930s.

- In 2006, Venezuela's Flag Day was moved to the 3rd of August, in honor of Miranda's 1806 disembarkation at La Vela de Coro.

- One of the Bolivarian missions, Mission Miranda, is named after him.

- Miranda's life was portrayed in the Venezuelan film Francisco de Miranda (2006), as well as in the unrelated film Miranda Returns (2007).

- Pensacola, Florida, has a square named after him.

- There are statues of Miranda in Cadiz (Spain), Caracas, Havana, London, Philadelphia, Patras (Greece), Pensacola Fla, São Paulo (Brazil), St. Petersburg (Russia), Paris and Valmy (France).

- The house where Miranda lived in London, 27 Grafton Street (now 58 Grafton Way),[32]Bloomsbury, has a blue plaque that bears his name,[33] and functions today as the Consulate of Venezuela in the United Kingdom.

Gallery

Monument to Francisco de Miranda. National Pantheon, Caracas, Venezuela.

Miranda's name transcribed beneath the Arc de Triomphe, column 4.

Bust of Francisco de Miranda, Bogotá, Colombia.

Epitaph of Francisco de Miranda in the Pantheon.

Miranda en La Carraca, by Arturo Michelena, 1896.

Plaza Miranda, Maracay, Venezuela.

Statue of Francisco de Miranda in Fitzroy Street, London.

Statue of Francisco de Miranda in Caracas.

Statue of Miranda in Valmy.

Statue of Miranda in Havana, Cuba.

Monument to Francisco de Miranda in La Vela de Coro, Venezuela.

Portrait of Miranda in 1792, by Georges Rouget (1835).

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Miranda, Francesco". Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 573–574. It cites the following references:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Miranda, Francesco". Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 573–574. It cites the following references:- Biggs, James. History of Miranda's Attempt in South America, London, 1809.

- The Marqués de Rojas, El General Miranda, Paris, 1884.

- The Marqués de Rojas Miranda dans la révolution française, Carácas, 1889.

- Robertson, W. S. Francisco de Miranda and the Revolutionizing of Spanish America, Washington, 1909.

^ Torregroza, Enver Joel; Ochoa, Pauline (2010). Formas de hispanidad. Universidad del Rosario.

^ abc "Limpieza de Sangre – Portal Archivo General de la Nación". www.agnve.gob.ve (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-06-19.

^ abcdefghijklmno Racine, Karen. Francisco de Miranda: A Transatlantic Life in the Age of Revolution Scholarly Resources Inc, Wilmington, DE, 2003

^ Torregroza, Enver Joel; Ochoa, Pauline (2010). Formas de hispanidad (in Spanish). Colombia: Universidad del Rosario - Center of Political and International Studies. p. 68. ISBN 978-958-738-120-7.

^ abcde Chocrón Cohen, José (2011). La identidad secreta de Francisco de Miranda (in Español). Alfa. ISBN 9789803543082. CS1 maint: Unrecognized language (link)

^ ab Noé, Natán (2015). "LA EXPERIENCIA JUDÍA abre puentes culturales" (PDF). Maguén Escudo Jewish Magazine. 175: 10–23.

^ ab Spence Robertson, William (1929). "The Life of Miranda". The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780815402916.

^ Miranda, Francisco (1963). The new democracy in America; travels of Francisco de Miranda in the United States, 1783-84. Norman, University of Oklahoma Press.

^ Wheeler, W. Reinald (1925). The Foreign Student In America (PDF). Association Press.

^ Yurman, Fernando. "UN LEGADO FANTASMAL" (PDF). Maguén Escudo (Center for Sephardic Studies in Caracas).

^ Alpert, Michael (2001). Crypto-judaism and the Spanish Inquisition. Palgrave.

^ Arbell, Mordehay (2002). The Jewish Nation of the Caribbean: The Spanish-Portuguese Jewish Settlements in the Caribbean and the Guianas. World Jewish Congress.

^ abcdefgh Thorning, Joseph F. Miranda: World Citizen. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, FL, 1952

^ Chávez p.209

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwx Hill, Peter P. (December 2016). "An Expedition to Liberate Venezuela Sails from New York, 1806". Historian. 78 (4): 671–689. doi:10.1111/hisn.12336. Retrieved 10 July 2017 – via EBSCO's Academic Serch Complete (subscription required)

^ See David Gilks, "Art and politics during the ‘First’ Directory: artists’ petitions and the quarrel over the confiscation of works of art from Italy in 1796 " French history 26(2012), pp. 53-78.

^ Marshall, John (1828). Royal naval biography, or, Memoirs of the services of all the flag-officers, superannuated rear-admirals, retired-captains, post-captains, and commanders, whose names appeared on the Admiralty list of sea officers at the commencement of the present year 1823, or who have since been promoted... (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown). Supplement, Part 2, pp. 404-6.

^ Parra-Pérez, Caracciolo. Historia de la Primera República de Venezuela (Caracas: Biblioteca de la Academia Nacional de la Historia,1959), 357–365.

^ Masur (1969), 98-102; and Lynch, Bolívar: A Life, 60-63.

^ "Octagon Museum - Curaçao Art". Retrieved 2016-10-01.

^ Trend J.B. Bolivar, 85, quoting contemporary English Colonel Belford Wilson and adding that many republican officers were in fact "imprisoned or shot."

^ Incorrectly, according to some observers. Trend, J.B. Bolivar and the Independence of Spanish America (New York: Macmillan Co, 1946), 80–83.

^ Branch, Hilary Dunsterville. Venezuela:The Bradt Travel Guide, 3rd ed. (Chalfont St Peter: Bradt Publications, 1999), 62. ISBN 1-898323-89-5

^ Dydyńsky, Krzysztof. Venezuela, 2nd ed. (Hawthorn:Lonely Planet Publications, 1998), 129. ISBN 0-86442-514-7

^ Rumazo González (2006), pp. 140-141.

^ Rumazo González (2006), p. 129.

^ Rumazo González (2006), p. 186.

^ Edsel González, Carlos. "Miranda Andrews, Francisco", Diccionario de Historia de Venezuela. Caracas: Fundacíon Polar, 1997. ISBN 980-6397-37-1

^ Fundación Polar. "Miranda Andrews, Leandro", Diccionario de Historia de Venezuela. Caracas: Fundacíon Polar, 1997. ISBN 980-6397-37-1

^ du Preez, Hercules Michael (January 2008). "Dr. James Barry:The early years revealed". South African Medical Journal. Health & Medical Publishing Group. 98 (1): 52–54. Text. Pdf.

^ de Pauw, Linda Grant (1998), "Nineteenth-century warfare", in de Pauw, Linda Grant, Battle cries and lullabies: women in war from prehistory to the present, Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, p. 146, ISBN 9780806131009.

^ Andrés Bello, Scholarship and Nation-Building in Nineteenth-Century Latin America, Ivan Jaksic, Cambridge Latin American Studies, 2006, ISBN 9780521027595, p33 [1]

^ "Francisco de Miranda Blue Plaque". londonremembers.com. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

Further reading

- Chavez, Thomas E. Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift. University of New Mexico Press, 2003.

Juan Carlos Chirinos. Miranda, el nómada sentimental. Editorial Norma, Caracas, 2006. ISBN 978-9806-77-9186 Parameter error in isbn: Invalid ISBN. / Ediciones Ulises, Sevilla, 2017 ISBN 978-8416-30-0587- Harvey, Robert. "Liberators: Latin America`s Struggle For Independence, 1810-1830". John Murray, London (2000). ISBN 0-7195-5566-3

- Miranda, Francisco de. (Judson P. Wood, translator. John S. Ezell, ed.) The New Democracy in America: Travels of Francisco de Miranda in the United States, 1783–84. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963.

- Racine, Karen. Francisco De Miranda: A Transatlantic Life in the Age of Revolution. Wilmington, Del: SR Books, 2003. ISBN 0842029095

- Robertson, William S. "Francisco de Miranda and the Revolutionizing of Spanish America" in Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1907, Vol. 1. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1908. 189–539.

- Robertson, William S. Life of Miranda, 2 vols. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1929.

- Rumazo González, Alfonso. Francisco de Miranda. Protolíder de la Independencia Americana (Biografía). Caracas: Ediciones de la Presidencia de la República, 2006.

- Smith, Denis. General Miranda's Wars: Turmoil and Revolt in Spanish America, 1750-1816. Toronto, Bev Editions (e-book), 2013.

- Thorning, Joseph F. Miranda: World Citizen. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1952.

- Moisei Alperovich . "Francisco de Miranda y Rusia", V Centenario del descubrimiento de América: encuentro de culturas y continentes. Editorial Progreso, (Moscu), shortened version in Spanish, (1989), ISBN 978-5010012489, Edit. Progreso, URSS, 380 pages. Russian Version : unabridged, (1986).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Francisco de Miranda. |

Colombeia (In Spanish) – The complete digitized files of Francisco de Miranda, mostly in Spanish, with translations of his documents written in English and French. More than 15 volumes in relation to Miranda's voyages, the French Revolution and the negotiations of Miranda with foreign nations, specially Great Britain.- Grogan, Samuel "Francisco de Miranda", History Text Archive

Another statue by Lorenzo Gonzalez (1977) on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia

"General Miranda's Expedition", Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 5, No. 31 (May 1860). An account of the Leander affair

Diarios: Una selección 1771 – 1800 (in Spanish) – Selections from the diaries of Francisco de Miranda, 1771–1800, Caracas: Monte Avila, 2006

UNESCO (2007), Colombeia: Generalissimo Francisco de Miranda's Archives, retrieved May 11, 2009

Full text archive of 'General Miranda's Expedition', from the Atlantic Monthly May 1860

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP