Kingdom of East Anglia

Kingdom of the East Angles Ēast Engla Rīce Regnum Orientalium Anglorum | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

6th century–918 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Kingdom of the Angles (6th century—869) Kingdom of the Danes (869–918) Vassal of Mercia (654–655, 794–796, 798–825) Vassal of the Danes (869–918) | ||||||||

| Capital | Rendlesham, Dommoc | ||||||||

| Common languages | Old English, Latin | ||||||||

| Religion | Anglo-Saxon paganism, Anglo-Saxon Christianity | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| List of monarchs of East Anglia | |||||||||

• ?–? | Wehha of East Anglia (first) | ||||||||

• 902–918 | Guthrum II (last) | ||||||||

• | 6th century | ||||||||

• | 918 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Kingdom of the East Angles (Old English: Ēast Engla Rīce; Latin: Regnum Orientalium Anglorum), today known as the Kingdom of East Anglia, was a small independent kingdom of the Angles comprising what are now the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk and perhaps the eastern part of the Fens.[1] The kingdom formed in the 6th century in the wake of the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain. It was ruled by the Wuffingas in the 7th and 8th centuries, but fell to Mercia in 794, and was conquered by the Danes in 869, forming part of the Danelaw. It was conquered by Edward the Elder and incorporated into the Kingdom of England in 918.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Settlement

1.2 Pagan rule

1.3 Christianization

1.4 Mercian aggression

1.5 Viking attacks and eventual settlement

1.6 Absorption into the Kingdom of England

2 Old East Anglian dialect

3 Geography

4 Sources

5 See also

6 Notes

7 References

8 Bibliography

History

The Kingdom of East Anglia was organized in the first or second quarter of the 6th century with Wehha listed as the first king of the East Angles, followed by Wuffa.[1]

Until 749 the kings of East Anglia were Wuffingas, named after the semi-historical Wuffa. During the early seventh century, under Rædwald of East Anglia, it was a powerful Anglo-Saxon kingdom. Rædwald, the first of the East Anglian kings to be baptised as a Christian, is considered by many experts to be the person who was buried within (or commemorated by) the ship burial at Sutton Hoo, near Woodbridge. During the decades that followed his death in around 624, East Anglia became increasingly dominated by the powerful kingdom of Mercia. Several of Rædwald's successors were killed in battle, such as Sigeberht (killed circa 641). Under Sigeberht's rule and the guidance of his bishop, Felix of Burgundy, Christianity was firmly established in East Anglia.

After Æthelberht II was killed by the Mercians in 794, and until 825, East Anglia ceased to be an independent kingdom, although it briefly reasserted its independence under Eadwald in 796. It survived until 869, when the Vikings defeated the East Anglians in battle and their king, Edmund the Martyr, was killed. After 879, the Vikings settled permanently in East Anglia. In 903 the exiled Æthelwold ætheling induced the East Anglian Danes to wage a disastrous war on his cousin Edward the Elder. By 917, after a succession of Danish defeats, East Anglia had submitted to Edward and was incorporated into the kingdom of England, afterwards becoming an earldom.

Settlement

East Anglia was settled by the Anglo-Saxons as early as around 450, earlier than many other regions. It emerged from the settlement and political consolidation of Angles in the approximate area of the former territory of the Iceni and the Roman civitas with its centre at Venta Icenorum, close to Caistor St Edmund.[2] According to Bede, the East Angles (as well as the Middle Angles, the Mercians and the Northumbrians) were descended from natives of Angeln (now in modern Germany).[os 1] The first reference to the East Angles is from around 704–713, in the Whitby Life of St Gregory.[eek 1]

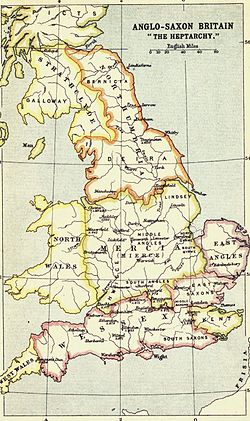

The East Angles formed one of the seven kingdoms known to post-mediaeval historians as the Heptarchy, a scheme used by Henry of Huntingdon in the twelfth century. Some modern historians have questioned whether seven independent kingdoms ever really existed contemporaneously, and claim that the political situation was much more complicated.[eek 2]

Pagan rule

The golden belt buckle from the Sutton Hoo ship-burial

The East Angles were initially ruled by the pagan Wuffingas dynasty, apparently named after an early king, Wuffa, although his name could have been an invention to explain the dynastic name, which means 'descendants of the wolf'.[2] An indispensable main source of information on the early history of the kingdom and its rulers is Bede's Ecclesiastical History,[note 1] but he provided few facts relating to the chronology of the East Anglian kings or the length of their reigns.[kease 1] Nothing is known of the earliest kings of East Anglia, or how the kingdom was organised, although a possible indication of the original centre of royal power is the concentration of ship-burials at Snape and Sutton Hoo in eastern Suffolk. The "North Folk" and "South Folk" may have existed before the arrival of the first East Anglian kings.[kease 2]

The most powerful of the Wuffingas kings was Rædwald, 'the son of Tytil, whose father was Wuffa',[2] according to the Ecclesiastical History. For a brief period in the early seventh century, whilst Rædwald ruled, East Anglia was among the most powerful kingdoms in Anglo-Saxon England: Rædwald was described by Bede as the overlord of the kingdoms south of the Humber.[eek 3] In 616, he had been strong enough to defeat and kill the Northumbrian king Æthelfrith at the Battle of the River Idle and enthrone Edwin of Northumbria.[eek 4] He was probably the individual honoured by the sumptuous ship burial at Sutton Hoo.[eek 5] It has been suggested by Blair, on the strength of the parallels between some of the objects found under Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo and those discovered at Vendel in Sweden, that the Wuffingas may have been the descendants of an eastern Swedish royal family. However, as those items previously thought to have come from Sweden are now believed to have been made in England, it seems less likely that the Wuffingas were of Swedish origin.[kease 3]

The Heptarchy, according to Bartholomew's A literary & historical atlas of Europe (1914)

Christianization

During the seventh century, Anglo-Saxon Christianity was successfully established. The extent to which paganism was displaced in East Anglia is exemplified by a lack of any East Anglian settlements that are named after the old gods.[rga 1]

Rædwald was the first East Anglian king to be baptised, in 604. He maintained a Christian altar, but at the same time continued to worship pagan gods.[kease 4] From 616, when pagan monarchs briefly returned in Kent and Essex, until Rædwald's death, East Anglia was the only Anglo-Saxon kingdom with a reigning baptised king. On his death in around 624, he was succeeded by his son Eorpwald, who was soon afterwards converted from paganism as a result of the influence of Edwin,[2] but his new religion was evidently opposed in East Anglia and Eorpwald met his death at the hands of a pagan, Ricberht. After three years of apostasy, Christianity prevailed with the accession of Eorpwald's brother (or step-brother) Sigeberht, who had been baptised during his exile in Francia.[eek 6] Sigeberht oversaw the establishment of the first East Anglian see for Felix of Burgundy at Dommoc, probably at Dunwich.[os 2] He later abdicated in favour of his brother Ecgric and retired to a monastery.[os 3]

Mercian aggression

The eminence achieved by East Anglia under Rædwald did not last long, as his dynasty fell victim to the rising power of Penda of Mercia and his successors. Throughout the mid-seventh to early ninth centuries, Mercian power grew until a vast region from the River Thames to the Humber, including East Anglia and the south-east, became a zone of Mercian hegemony.[mercia 1] In the early 640s Penda defeated and killed both Ecgric and Sigeberht,[kease 4] who was later venerated as a saint.[3] Ecgric's successor Anna and Anna's son Jurmin were killed together in 654 at the Battle of Bulcamp, near Blythburgh.[os 4] Having eliminated Anna's challenge to his rising power, Penda then subjected the East Anglians to Mercian overlord-ship.[kease 5] In 655 Æthelhere of East Anglia joined Penda in a campaign against Oswiu, which ended in a disastrous Mercian defeat at the Battle of the Winwaed, in which both Penda and his ally Æthelhere were killed.[eek 7]

The last Wuffingas king was Ælfwald, who died in 749.[rga 2] During the late 7th and 8th centuries East Anglia continued to be overshadowed by Mercian hegemony until, in 794, Offa of Mercia had the East Anglian king Æthelberht executed and then took control of the kingdom for himself.[mercia 2] A brief revival of East Anglian independence under Eadwald after Offa's death in 796 was soon suppressed by the new Mercian king, Coenwulf.[mercia 3]

The independence of the East Anglians was restored by a successful rebellion against Mercia led by Æthelstan in 825. Beornwulf of Mercia's attempt to restore Mercian control over East Anglia resulted in his defeat and death, and his successor Ludeca met the same end in 827. The East Angles appealed to Egbert of Wessex for protection against the Mercians and Æthelstan then acknowledged Egbert as his overlord. Whilst Wessex took control of the south-eastern kingdoms which had been absorbed by Mercia during the eighth century, East Anglia could maintain its independence.[mercia 4]

Viking attacks and eventual settlement

England in 878, when East Anglia was ruled by Guthrum

In 865, East Anglia was invaded by the Danish Great Heathen Army, which occupied winter quarters and secured horses before departing for Northumbria.[eek 8] The Danes returned to East Anglia in 869, wintering at Thetford before being attacked by the forces of Edmund of East Anglia, who was defeated and killed at Hægelisdun (identified variously as Bradfield St Clare in 983, which is near to his final resting place at Bury St Edmunds; Hellesdon in Norfolk (documented as Hægelisdun c.985); Hoxne in Suffolk;[4] and now with Maldon in Essex).[2][rga 3][5] From this point onwards, East Anglia effectively ceased to be an independent kingdom. Having defeated the East Angles, the Danes then installed puppet-kings to govern on their behalf, while they resumed their campaigns against Mercia and Wessex.[6] In 878 the last portion of the Great Heathen Army to remain active was defeated by Alfred the Great and withdrew from Wessex after making a peace treaty. In 880 the Vikings returned to East Anglia under the leadership of Guthrum, who, according to the mediaeval historian Pauline Stafford, "swiftly adapted to territorial kingship and its trappings, including the minting of coins".[7]

In addition to the traditional territory of East Anglia, Cambridgeshire and parts of Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire, Guthrum's kingdom probably included Essex, the only portion of Wessex which had come under Danish control.[8] A peace treaty made between Alfred and Guthrum sometime in the 880s.[9]

Absorption into the Kingdom of England

In the early tenth century, the East Anglian Danes came under increasing pressure from Edward the Elder, king of Wessex. In 902 Edward's cousin Æthelwold ætheling, who had been driven into exile after an unsuccessful bid for the throne, arrived in Essex after a stay in Northumbria. He was apparently accepted as king by some or all of the Danes in England and in 903 he induced the East Anglian Danes to wage war on Edward. This ended in disaster, with the death of Æthelwold and of Eohric of East Anglia in a battle in the Fens.[ase 1]

Between 911 and 919, Edward expanded his control over the rest of England south of the Humber, establishing in Essex and Mercia burhs, often designed to control the use of a river by the Danes.[10] In 917, the Danish position in the area suddenly collapsed. A rapid succession of defeats culminated in the loss of the territories of Northampton and Huntingdon, along with the remainder of Essex: a Danish king, probably from East Anglia, was killed at Tempsford. Despite reinforcement from overseas, the Danish counter-attacks were crushed, and following the defection of many of their English subjects as Edward's army advanced, the Danes of East Anglia and Cambridge both capitulated.[ase 2]

The territory of East Anglia was absorbed into the kingdom of England. Norfolk and Suffolk became part of the new earldom of East Anglia, when in 1017, Thorkell the Tall was made earl of East Anglia by Cnut the Great.[11] The restoration of the ecclesiastical structure in the region saw the two former East Anglian bishoprics replaced by a single one based at North Elmham.[2]

Old East Anglian dialect

The East Angles spoke Old English. Their language is historically important, as they were among the first Germanic settlers to arrive in Britain during the fifth century: according to Kortmann and Schneider, East Anglia "can seriously claim to be the first place in the world where English was spoken".[12]

The evidence for dialects in Old English comes from the study of texts, place-names, personal names and coins.[oea 1] A. H. Smith was the first to recognise the existence of a separate Old East Anglian dialect, in addition to the previously recognised dialects of Northumbrian, Mercian, West Saxon and Kentish. He acknowledged that his proposal of such a dialect was tentative, acknowledging that "the linguistic boundaries of the original dialects could not have enjoyed prolonged stability".[oea 2] As no East Anglian manuscripts, Old English inscriptions or literary records such as charters have survived to modern times, there is little evidence to support the existence of an Old East Anglian dialect. According to a study made by Von Feilitzen in the 1930s, the recording of many place-names in Domesday Book was "ultimately based on the evidence of local juries" and so the spoken form of Anglo-Saxon places and people was partly preserved in this way.[oea 3] Evidence from Domesday Book and later sources does suggest that a dialect boundary once existed, corresponding with a line that separates from their neighbours the English counties of Cambridgeshire (including the once sparsely-inhabited Fens), Norfolk and Suffolk.[oea 4]

Geography

A physical map of Eastern England

The kingdom of the East Angles bordered the North Sea to the north and the east, with the River Stour historically dividing it from the East Saxons to the south. The North Sea provided a "thriving maritime link to Scandinavia and the northern reaches of Germany", according to the historian Richard Hoggett. The kingdom's western boundary varied from the rivers Ouse, Lark and Kennett to further westwards, as far as the Cam in what is now Cambridgeshire. At its greatest extent, the kingdom comprised the modern-day counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and parts of eastern Cambridgeshire.[aeac 2]

Erosion along the eastern border and deposition along the north coast altered the shape of the East Anglian coastline during Roman and Anglo-Saxon times (and continues to do so today). During Saxon times the sea inundated the naturally low-lying Fens. As sea levels fell alluvium was deposited near major river estuaries and the 'Great Estuary' near Burgh Castle became slowed closed off by a large spit.[aeac 3]

Sources

No East Anglian charters (and few other documents) have survived to modern times and those mediaeval chronicles that refer to the East Angles are treated with great caution by scholars. Very few records from the Kingdom of the East Angles have survived, because of the complete destruction of the kingdom's monasteries and the disappearance of the two East Anglian sees as the result of Viking raids and settlement.[kease 6] The principal documentary source for the early period of the kingdom's history is Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written by Bede in the eighth century. East Anglia is first mentioned as a distinct political unit in the Tribal Hidage, which is thought to have been compiled somewhere in England during the seventh century.[shoo 1]

Anglo-Saxon sources that include information about the East Angles or events relating to the kingdom:[shoo 2]

- Ecclesiastical History of the English People

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

- The Tribal Hidage, where the East Angles are assessed at 30,000 hides, evidently superior in resources to lesser kingdoms such as Sussex and Lindsey.[eek 9]

- Historia Brittonum

Life of Foillan, written in the seventh century

Post-Norman sources (of variable historical validity):

- The 12th century Liber Eliensis

Florence of Worcester's Chronicle, written in the twelfth century

Henry of Huntingdon's Historia Anglorum, written in the twelfth century

Roger of Wendover's Flores Historiarum, written in the thirteenth century

See also

- List of monarchs of East Anglia

Notes

^ See Hoggett, The Archaeology of the East Anglian Conversion, pp. 24–27, for a detailed discussion of Bede's original sources and an account of the events in East Anglia that he refers to in the Ecclesiastical History.[aeac 1]

References

^ ab One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "East Anglia". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "East Anglia". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

^ abcdef Higham, N.J. (1999). "East Anglia, Kingdom of". In M. Lapidge; et al. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. London: Blackwell. pp. 154–155. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

^ Baring-Gould, Sabine (1843). The Lives of the Saints. 12 (Internet Archive ed.). Nimmo. p. 712. Retrieved 2011-07-08.

^ Hidden East Anglia – Part 5 – The Last Mystery: Where Did Edmund Die?

^ Keith Briggs, Was Hægelisdun in Essex? A new site for the martyrdom of Edmund. Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History volume XLII (2011), pages 277–291

^ Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard D.; Pedersen, Frederik (2005). Viking Empires. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

^ Stafford, in A Companion to the early Middle Ages, p. 205.

^ Hunter Blair, Peter; Keynes, Simon (2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-521-29219-1.

^ Lavelle, Ryan (2010). Alfred's wars: sources and interpretations of Anglo-Saxon warfare in the Viking Age. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. p. 325. ISBN 978-1-84383-569-1.

^ Wilson, David Mackenzie (1976). The Archaeology of Anglo-Saxon England. London: Methuen & Co Ltd. pp. 135–6. ISBN 978-0-416-15090-2.

^ Harper-Bill, Christopher; Van Houts, Elisabeth (2002). A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-84383-341-3.

^ Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W. (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English: a Multimedia Reference Tool. 1 Phonology. The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 163. ISBN 978-3-11-017532-5.

Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (2001). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe. London, New York: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-8264-7765-1.

^ Brown and Farr, Mercia, pp. 2, 4.

^ Brown and Farr, Mercia, p. 215.

^ Brown and Farr, Mercia, p. 310.

^ Brown and Farr, Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe, pp. 222, 313.

Carver, M. O. H., ed. (1992). The Age of Sutton Hoo: the Seventh Century in North-Western Europe. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-361-2.

^ Carver, The Age of Sutton Hoo, p. 3.

^ Carver, Age of Sutton Hoo, pp. 4–5.

- Fisiak, Old East Anglian

^ Fisiak, Old East Anglian, p. 22.

^ Fisiak, Old East Anglian, pp. 19–20.

^ Fisiak, Old East Anglian, pp. 22–23.

^ Fisiak, Old East Anglian, p. 27.

Hoggett, Richard (2010). The Archaeology of the East Anglian Conversion. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-595-0.

^ Hoggett, East Anglian Conversion, pp. 24–27.

^ Hoggett, The Archaeology of the East Anglian Conversion, pp. 1–2.

^ Hoggett, The Archaeology of the East Anglian Conversion, p. 2.

Hoops, Johannes (1986) [1911–1919]. Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde (in English and German). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co. ISBN 978-3-11-010468-4.

^ Hoops, Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, Volume 24, p. 68.

^ Hoops, Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, Volume 6, p. 328.

^ Hoops, Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, Volume 6, p. 328.

Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24211-0.

^ Kirby, p. 20.

^ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 4.

^ Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 54.

^ Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 52.

^ Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 55.

^ Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 66.

^ Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, pp. 78–79.

^ Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 173.

^ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 11.

Stenton, Sir Frank (1988). Anglo-Saxon England. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821716-9.

^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 321–2.

^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 328.

Yorke, Barbara (2002). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16639-3.

^ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 58.

^ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 61.

^ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 61.

^ ab Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 62.

^ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, p. 63.

^ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, p. 58.

Warner, Peter (1996). The Origins of Suffolk. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3817-4.

^ Warner, Suffolk, p. 61.

^ Warner, The Origins of Suffolk, p. 109.

^ Warner, The Origins of Suffolk, p. 84.

^ Warner, The Origins of Suffolk, p. 142.

Bibliography

Hadley, Dawn (2009). "Viking Raids and Conquest". In Stafford, Pauline. A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500–c.1100. Chichester: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0628-3.

Williams, Gareth (2001). "Mercian Coinage and Authority". In Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann. Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Leicester: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-8264-7765-1.

Coordinates: 52°30′N 01°00′E / 52.500°N 1.000°E / 52.500; 1.000

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP