Oxyrhynchus Papyri

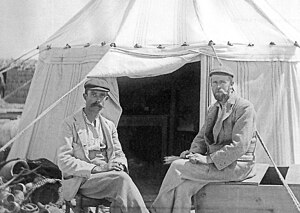

Grenfell (left) and Hunt (right) in about 1896

Excavations at Oxyrhynchus 1, ca. 1903.

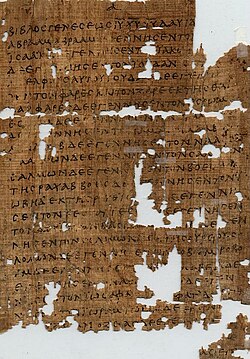

The Oxyrhynchus Papyri are a group of manuscripts discovered during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by papyrologists Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt at an ancient rubbish dump near Oxyrhynchus in Egypt (28°32′N 30°40′E / 28.533°N 30.667°E / 28.533; 30.667, modern el-Bahnasa).

The manuscripts date from the time of the Ptolemaic (3rd century BC) and Roman periods of Egyptian history (from 32 BC to the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 640 AD).

Only an estimated 10% are literary in nature. Most of the papyri found seem to consist mainly of public and private documents: codes, edicts, registers, official correspondence, census-returns, tax-assessments, petitions, court-records, sales, leases, wills, bills, accounts, inventories, horoscopes, and private letters.[1]

Although most of the papyri were written in Greek, some texts written in Egyptian (Egyptian hieroglyphics, Hieratic, Demotic, mostly Coptic), Latin and Arabic were also found. Texts in Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac and Pahlavi have so far represented only a small percentage of the total.[2]

Since 1898 academics have puzzled together and transcribed over 5000 documents from what were originally hundreds of boxes of papyrus fragments the size of large cornflakes. This is thought to represent only 1 to 2 percent of what is estimated to be at least half a million papyri still remaining to be conserved, transcribed, deciphered and catalogued.

Oxyrhynchus Papyri are currently housed in institutions all over the world. A substantial number are housed in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University. There is an on-line table of contents briefly listing the type of contents of each papyrus or fragment.[3]

Contents

1 Administrative texts

2 Secular Texts

2.1 Greek

2.1.1 Historiography

2.1.2 Mathematics

2.1.3 Drama

2.1.4 Poetry

2.2 Latin

3 Christian texts

3.1 Old Testament

3.1.1 Old Testament Deuterocanon (or, Apocrypha)

3.1.2 Other related papyri

3.2 New Testament

3.2.1 New Testament Apocrypha

3.2.2 Other related texts

4 See also

5 References

6 External links

Administrative texts

Administrative Documents assembled and transcribed from the Oxyrhynchus excavation so far include:

- The contract of a wrestler agreeing to throw his next match for a fee.[4]

- Various and sundry ancient recipes for treating haemorrhoids, hangovers and cataracts.[5]

- Details of a corn dole mirroring a similar program in the Roman capital.[6]

Secular Texts

Although most of the texts uncovered at Oxyrhynchus were non-literary in nature, the archaeologists succeeded in recovering a large corpus of literary works that had previously been thought to have been lost. Many of these texts had previously been unknown to modern scholars.

Greek

Several fragments can be traced to the work of Plato, for instance the Republic, Phaedo, or the dialogue Gorgias, dated around 200-300 CE.[7]

Historiography

Another important discovery was a papyrus codex containing a significant portion of the treatise The Constitution of the Athenians, which was attributed to Aristotle and had previously been thought to have been lost forever.[8] A second, more extensive papyrus text was purchased in Egypt by an American missionary in 1890. E. A. Wallis Budge of the British Museum acquired it later that year, and the first edition of it by British paleographer Frederic G. Kenyon was published in January, 1891.[9] The treatise revealed a massive quantity of reliable information about historical periods that classicists previously had very little knowledge of. Two modern historians even went so far as to state that "the discovery of this treatise constitutes almost a new epoch in Greek historical study."[10] In particular, 21–22, 26.2–4, and 39–40 of the work contain factual information not found in any other extant ancient text.[11]

The discovery of a historical work known as the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia also revealed new information about classical antiquity. The identity of the author of the work is unknown; many early scholars proposed that it may have been written by Ephorus or Theopompus,[12] but many modern scholars are now convinced that it was written by Cratippus.[13] The work has won praise for its style and accuracy[14] and has even been compared favorably with the works of Thucydides.[15]

Mathematics

One of the oldest surviving fragments of Euclid's Elements, found at Oxyrhynchus and dated to circa AD 100 (P. Oxy. 29). The diagram accompanies Book II, Proposition 5.[16]

The findings at Oxyrhynchus also turned up the oldest and most complete diagrams from Euclid's Elements.[16] Fragments of Euclid discovered led to a re-evaluation of the accuracy of ancient sources for The Elements, revealing that the version of Theon of Alexandria has more authority than previously believed, according to Thomas Little Heath.[17]

Drama

Lines 96–138 of the Ichneutae on a fragment of Papyrus Oxyrhynchus IX 1174 col. iv–v, which provides the majority of the surviving portion of the play

The classical author who has most benefited from the finds at Oxyrhynchus is the Athenian playwright Menander (342–291 BC), whose comedies were very popular in Hellenistic times and whose works are frequently found in papyrus fragments. Menander's plays found in fragments at Oxyrhynchus include Misoumenos, Dis Exapaton, Epitrepontes, Karchedonios, Dyskolos and Kolax. The works found at Oxyrhynchus have greatly raised Menander's status among classicists and scholars of Greek theatre.

Another notable text uncovered at Oxyrhynchus was Ichneutae, a previously unknown play written by Sophocles. The discovery of Ichneutae was especially significant since Ichneutae is a satyr play, making it only one of two extant satyr plays, with the other one being Euripides's Cyclops.[18][19]

Extensive remains of the Hypsipyle of Euripides and a life of Euripides by Satyrus the Peripatetic were also found at Oxyrhynchus.

Poetry

P. Oxy. 20, verso

- Poems of Pindar. Pindar was the first known Greek poet to reflect on the nature of poetry and on the poet's role.

- Fragments of Sappho, Greek poet from the island of Lesbos famous for her poems about love.

- Fragments of Alcaeus, an older contemporary and an alleged lover of Sappho, with whom he may have exchanged poems.

- Larger pieces of Alcman, Ibycus, and Corinna.

- Passages from Homer's Iliad. See Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 20 – Iliad II 730-828 and Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 21 – Iliad II 745-764

Latin

An epitome of seven of the 107 lost books of Livy was the most important literary find in Latin.

Christian texts

Among the Christian texts found at Oxyrhynchus, were fragments of early non-canonical Gospels, Oxyrhynchus 840 (3rd century AD) and Oxyrhynchus 1224 (4th century AD). Other Oxyrhynchus texts preserve parts of Matthew 1 (3rd century: P2 and P401), 11–12 and 19 (3rd to 4th century: P2384, 2385); Mark 10–11 (5th to 6th century: P3); John 1 and 20 (3rd century: P208); Romans 1 (4th century: P209); the First Epistle of John (4th-5th century: P402); the Apocalypse of Baruch (chapters 12–14; 4th or 5th century: P403); the Gospel according to the Hebrews (3rd century AD: P655); The Shepherd of Hermas (3rd or 4th century: P404), and a work of Irenaeus, (3rd century: P405). There are many parts of other canonical books as well as many early Christian hymns, prayers, and letters also found among them.

All manuscripts classified as "theological" in the Oxyrhynchus Papyri are listed below. A few manuscripts that belong to multiple genres, or genres that are inconsistently treated in the volumes of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, are also included. For example, the quotation from Psalm 90 (P. Oxy. XVI 1928) associated with an amulet, is classified according to its primary genre as a magic text in the Oxyrhynchus Papyri; however, it is included here among witnesses to the Old Testament text. In each volume that contains theological manuscripts, they are listed first, according to an English tradition of academic precedence (see Doctor of Divinity).

Old Testament

P. Oxy. VI 846: Amos 2 (LXX)

The original Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) was translated into Greek between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC. This translation is called the Septuagint (or LXX, both 70 in Latin), because there is a tradition that seventy Jewish scribes compiled it in Alexandria. It was quoted in the New Testament and is found bound together with the New Testament in the 4th and 5th century Greek uncial codices Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus and Vaticanus. The Septuagint included books, called the Apocrypha or Deuterocanonical by Christians, which were later not accepted into the Jewish canon of sacred writings (see next section). Portions of Old Testament books of undisputed authority found among the Oxyrhynchus Papyri are listed in this section.

- The first number (Vol) is the volume of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri in which the manuscript is published.

- The second number (Oxy) is the overall publication sequence number in Oxyrhynchus Papyri.

- Standard abbreviated citation of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri is:

- P. Oxy. <volume in Roman numerals> <publication sequence number>.

- Context will always make clear whether volume 70 of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri or the Septuagint is intended.

- P. Oxy. VIII 1073 is an Old Latin version of Genesis, other manuscripts are probably copies of the Septuagint.

- Dates are estimated to the nearest 50 year increment.

- Content is given to the nearest verse where known.

| Vol | Oxy | Date | Content | Institution | City, State | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | 656 | 150 | Gen 14:21–23; 15:5–9; 19:32–20:11; 24:28–47; 27:32–33, 40–41 | Bodleian Library; MS.Gr.bib.d.5(P) | Oxford | UK |

| VI | 845 | 400 | Psalms 68; 70 | Egyptian Museum; JE 41083 | Cairo | Egypt |

| VI | 846 | 550 | Amos 2 | University of Pennsylvania; E 3074 | Philadelphia Pennsylvania | U.S. |

| VII | 1007 | 400 | Genesis 2-3 | British Museum; Inv. 2047 | London | UK |

| VIII | 1073 | 350 | Gen 5–6 Old Latin | British Museum; Inv. 2052 | London | UK |

| VIII | 1074 | 250 | Exodus 31–32 | University of Illinois; GP 1074 | Urbana, Illinois | U.S. |

| VIII | 1075 | 250 | Exodus 11:26–32 | British Library; Inv. 2053 (recto) | London | UK |

| IX | 1166 | 250 | Genesis 16:8–12 | British Library; Inv. 2066 | London | UK |

| IX | 1167 | 350 | Genesis 31 | Princeton Theological Seminary Pap. 9 | Princeton New Jersey | U.S. |

| IX | 1168 | 350 | Joshua 4-5 vellum | Princeton Theological Seminary Pap. 10 | Princeton New Jersey | U.S. |

| X | 1225 | 350 | Leviticus 16 | Princeton Theological Seminary Pap. 12 | Princeton New Jersey | U.S. |

| X | 1226 | 300 | Psalms 7–8 | Liverpool University Class. Gr. Libr. 4241227 | Liverpool | UK |

| XI | 1351 | 350 | Lev 27 vellum | Ambrose Swasey Library; 886.4 Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School | Rochester New York | U.S. |

| XI | 1352 | 325 | Pss 82–83 vellum | Egyptian Museum; JE 47472 | Cairo | Egypt |

| XV | 1779 | 350 | Psalm 1 | United Theological Seminary | Dayton, Ohio | U.S. |

| XVI | 1928 | 500 | Ps 90 amulet | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XVII | 2065 | 500 | Psalm 90 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XVII | 2066 | 500 | Ecclesiastes 6–7 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XXIV | 2386 | 500 | Psalms 83–84 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| L | 3522 | 50 | Job 42.11–12 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LX | 4011 | 550 | Ps 75 interlinear | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXV | 4442 | 225 | Ex 20:10–17, 18–22 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXV | 4443 | 100 | Esther 6–7 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

Old Testament Deuterocanon (or, Apocrypha)

This name designates several, unique writings (e.g., the Book of Tobit) or different versions of pre-existing writings (e.g., the Book of Daniel) found in the canon of the Jewish scriptures (most notably, in the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Tanakh). Although those writings were no longer viewed as having a canonical status amongst Jews by the beginning of the second century A.D., they retained that status for much of the Christian Church. They were and are accepted as part of the Old Testament canon by the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox churches. Protestant Christians, however, follow the example of the Jews and do not accept these writings as part of the Old Testament canon.

- PP. Oxy. XIII 1594 and LXV 4444 are vellum ("vellum" noted in table).

- Both copies of Tobit are different editions to the known Septuagint text ("not LXX" noted in table).

| Vol | Oxy | Date | Content | Institution | City, State | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III | 403 | 400 | Apocalypse of Baruch 12–14 | St. Mark's Library General Theological Seminary | New York City | U.S. |

| VII | 1010 | 350 | 2 Esdras 16:57–59 | Bodleian Library MS.Gr.bib.g.3(P) | Oxford | UK |

| VIII | 1076 | 550 | Tobit 2 not LXX | John Rylands University Library 448 | Manchester | UK |

| XIII | 1594 | 275 | Tobit 12 vellum, not LXX | Cambridge University Library Add.MS. 6363 | Cambridge | UK |

| XIII | 1595 | 550 | Ecclesiasticus 1 | Palestine Institute Museum Pacific School of Religion | Berkeley California | U.S. |

| XVII | 2069 | 400 | 1 Enoch 85.10–86.2, 87.1–3 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XVII | 2074 | 450 | Apostrophe to Wisdom [?] | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXV | 4444 | 350 | Wisdom 4:17–5:1 vellum | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| Vol | Oxy | Date | Content | Institution | City, State | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IX | 1173 | 250 | Philo | Bodleian Library | Oxford | UK |

| XI | 1356 | 250 | Philo | Bodleian Library | Oxford | UK |

| XVIII | 2158 | 250 | Philo | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XXXVI | 2745 | 400 | onomasticon of Hebrew names | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

New Testament

Papyrus Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P

1: Matthew 1

1: Matthew 1The Oxyrhynchus Papyri have provided the most numerous sub-group of the earliest copies of the New Testament. These are surviving portions of codices (books) written in Greek uncial (capital) letters on papyrus. The first of these were excavated by Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt in Oxyrhynchus, at the turn of the 20th century. Of the 127 registered New Testament papyri, 52 (41%) are from Oxyrhynchus. The earliest of the papyri are dated to the middle of the 2nd century, so were copied within about a century of the writing of the original New Testament documents.[20]

Grenfell and Hunt discovered the first New Testament papyrus (Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P

- The third column (CRG) refers to the now standard sequences of Caspar René Gregory.

Pdisplaystyle mathfrak Pindicates a papyrus manuscript, a number beginning with zero indicates vellum.

- The CRG number is an adequate abbreviated citation for New Testament manuscripts.

- Content is given to the nearest chapter; verses are sometimes listed.

| Vol | Oxy | CRG | Date | Content | Institution | City, State | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 2 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  1 1 | 250 | Matthew 1 | University of Pennsylvania | Philadelphia Pennsylvania | U.S. |

| I | 3 | 069 | 500 | Mark 10:50.51; 11:11.12 | Frederick Haskell Oriental Institute University of Chicago; 2057 | Chicago Illinois | U.S. |

| II | 208=1781 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  5 5 | 250 | John 1, 16, 20 | British Library | London | UK |

| II | 209 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  10 10 | 350 | Romans 1 | Houghton Library, Harvard | Cambridge Massachusetts | U.S. |

| III | 401 | 071 | 500 | Matthew 10-11 † | Harvard Semitic Museum; 3735 | Cambridge Massachusetts | U.S. |

| III | 402 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  9 9 | 250 | 1 John 4 | Houghton Library, Harvard | Cambridge Massachusetts | U.S. |

| IV | 657 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  13 13 | 250 | Hebrews 2–5, 10–12 | British Library | London | UK |

| VI | 847 | 0162 | 300 | John 2 | Metropolitan Museum of Art | New York | U.S. |

| VI | 848 | 0163 | 450 | Revelation 16 | Metropolitan Museum of Art | New York | U.S. |

| VII | 1008 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  15 15 | 250 | 1 Corinthians 7–8 | Egyptian Museum | Cairo | Egypt |

| VII | 1009 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  16 16 | 300 | Philippians 3–4 | Egyptian Museum | Cairo | Egypt |

| VIII | 1078 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  17 17 | 350 | Hebrews 9 | Cambridge University Library, Cambridge | Cambridge | UK |

| VIII | 1079 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  18 18 | 300 | Revelation 1 | British Library | London | UK |

| VIII | 1080 | 0169 | 350 | Revelation 3–4 | Robert Elliott Speer Library Princeton Theological Seminary | Princeton | U.S. |

| IX | 1169 | 0170 | 500 | Matthew 6 | Robert Elliott Speer Library Princeton Theological Seminary | Princeton | U.S. |

| IX | 1170 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  19 19 | 400 | Matthew 10–11 | Bodleian Library | Oxford | UK |

| IX | 1171 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  20 20 | 250 | James 2–3 | Harvey S. Firestone Memorial Library, Princeton | Princeton New Jersey | U.S. |

| X | 1227 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  21 21 | 400 | Matthew 12 | Muhlenberg College | Allentown Pennsylvania | U.S. |

| X | 1228 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  22 22 | 250 | John 15–16 | Glasgow University Library | Glasgow | UK |

| X | 1229 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  23 23 | 250 | James 1 | University of Illinois | Urbana, Illinois | U.S. |

| X | 1230 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  24 24 | 350 | Revelation 5–6 | Franklin Trask Library Andover Newton Theological School | Newton Massachusetts | U.S. |

| XI | 1353 | 0206 | 350 | 1 Peter 5 | United Theological Seminary | Dayton, Ohio | U.S. |

| XI | 1354 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  26 26 | 600 | Romans 1 | Joseph S. Bridwell Library Southern Methodist University | Dallas, Texas | U.S. |

| XI | 1355 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  27 27 | 250 | Romans 8–9 | Cambridge University Library | Cambridge | UK |

| XIII | 1596 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  28 28 | 250 | John 6 | Palestine Institute Museum Pacific School of Religion | Berkeley California | U.S. |

| XIII | 1597 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  29 29 | 250 | Acts 26 | Bodleian Library | Oxford | UK |

| XIII | 1598 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  30 30 | 250 | 1 Ths 4–5; 2 Ths 1 | Ghent University Library | Ghent | Belgium |

| XV | 1780 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  39 39 | 250 | John 8 | Museum of the Bible | Washington, D.C. | U.S. |

| XV | 1781=208 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  5 5 | 250 | John 1, 16, 20 | British Library | London | UK |

| XVIII | 2157 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  51 51 | 400 | Galatians 1 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XXIV | 2383 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  69 69 | 250 | Luke 22 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XXIV | 2384 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  70 70 | 250 | Matthew 2–3, 11–12, 24 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XXIV | 2385 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  71 71 | 350 | Matthew 19 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XXXIV/LXIV | 2683/4405 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  77 77 | 200 | Matthew 23 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XXXIV | 2684 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  78 78 | 300 | Jude | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| L | 3523 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  90 90 | 150 | John 18–19 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXV | 4449 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  100 100 | 300 | James 3–5 | Sackler Library Papyrology Rooms | Oxford | UK |

| LXIV | 4401 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  101 101 | 250 | Matthew 3–4 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXIV | 4402 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  102 102 | 300 | Matthew 4 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXIV | 4403 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  103 103 | 200 | Matthew 13–14 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXIV | 4404 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  104 104 | 150 | Matthew 21? | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXIV | 4406 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  105 105 | 500 | Matthew 27–28 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXV | 4445 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  106 106 | 250 | John 1 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXV | 4446 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  107 107 | 250 | John 17 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXV | 4447 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  108 108 | 250 | John 17/18 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXV | 4448 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  109 109 | 250 | John 21 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXVI | 4494 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  110 110 | 350 | Matthew 10 | Sackler Library Papyrology Rooms | Oxford | UK |

| LXVI | 4495 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  111 111 | 250 | Luke 17 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXVI | 4496 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  112 112 | 450 | Acts 26–27 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXVI | 4497 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  113 113 | 250 | Romans 2 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXVI | 4498 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  114 114 | 250 | Hebrews 1 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXVI | 4499 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  115 115 | 300 | Revelation 2–3, 5–6, 8–15 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXVI | 4500 | 0308 | 350 | Revelation 11:15–18 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXXI | 4803 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  119 119 | 250 | John 1:21–28, 38–44 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXXI | 4804 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  120 120 | 350 | John 1:25–28, 33-38, 42–44 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXXI | 4805 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  121 121 | 250 | John 19:17–18, 25–26 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXXI | 4806 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  122 122 | 4th/5th century | John 21:11–14, 22–24 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXXII | 4844 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  123 123 | 4th/5th century | 1 Corinthians 14:31–34; 15:3–6 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXXII | 4845 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  124 124 | 4th/5th century | 2 Corinthians 11:1-4. 6-9 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXXIII | 4934 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  125 125 | 3rd/4th century | 1 Peter 1:23-2:5.7-12 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXXIV | 4968 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  127 127 | 5th century | Acts 10–17 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXXXI | 5258 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  132 132 | 3rd/4th century | Ephesians 3:21–4:2, 14–16 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| LXXXI | 5259 | Pdisplaystyle mathfrak P  133 133 | 3rd century | 1 Timothy 3:13–4:8 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

New Testament Apocrypha

The Oxyrhynchus Papyri collection contains around twenty manuscripts of New Testament apocrypha, works from the early Christian period that presented themselves as biblical books, but were not eventually received as such by the orthodoxy. These works found at Oxyrhynchus include the gospels of Thomas, Mary, Peter, James, The Shepherd of Hermas, and the Didache. Among this collection are also a few manuscripts of unknown gospels. The three manuscripts of Thomas represent the only known Greek manuscripts of this work; the only other surviving manuscript of Thomas is a nearly complete Coptic manuscript from the Nag Hammadi find.[22] P. Oxy. 4706, a manuscript of The Shepherd of Hermas, is notable because two sections believed by scholars to have been often circulated independently, Visions and Commandments, were found on the same roll.[23]

- P. Oxy. V 840 and P. Oxy. XV 1782 are vellum

- 2949?, 3525, 3529? 4705, and 4706 are rolls, the rest codices.

| Vol | Oxy | Date | Content | Institution | City, State | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Early Writings | ||||||

| LXIX | 4705 | 250 | Shepherd, Visions 1:1, 8–9 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXIX | 4706 | 200 | The Shepherd of Hermas Visions 3–4; Commandments 2; 4–9 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| L | 3526 | 350 | Shepherd, Commandments 5–6 [same codex as 1172] | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XV | 1783 | 325 | Shepherd, Commandments 9 | |||

| IX | 1172 | 350 | Shepherd, Parables 2:4–10 [same codex as 3526] | British Library; Inv. 224 | London | UK |

| LXIX | 4707 | 250 | Shepherd, Parables 6:3–7:2 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XIII | 1599 | 350 | Shepherd, Parables 8 | |||

| L | 3527 | 200 | Shepherd, Parables 8:4–5 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| L | 3528 | 200 | Shepherd, Parables 9:20–22 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| III | 404 | 300 | Shepherd | |||

| XV | 1782 | 350 | Didache 1–3 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

Pseudepigrapha | ||||||

| I | 1 | 200 | Gospel of Thomas | Bodleian Library Ms. Gr. Th. e 7 (P) | Oxford | UK |

| IV | 654 | 200 | Gospel of Thomas | British Museum; Inv. 1531 | London | UK |

| IV | 655 | 200 | Gospel of Thomas | Houghton Library, Harvard SM Inv. 4367 | Cambridge Massachusetts | U.S. |

| XLI | 2949 | 200 | Gospel of Peter? | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| L | 3524 | 550 | Gospel of James 25:1 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| L | 3525 | 250 | Gospel of Mary | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LX | 4009 | 150 | Gospel of Peter? | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| I | 6 | 450 | Acts of Paul and Thecla | |||

| VI | 849 | 325 | Acts of Peter | |||

| VI | 850 | 350 | Acts of John | |||

| VI | 851 | 500 | Apocryphal Acts | |||

| VIII | 1081 | Gnostic Gospel | ||||

| II | 210 | 250 | Unknown gospel | Cambridge University Library Add. Ms. 4048 | Cambridge | UK |

| V | 840 | 200 | Unknown gospel | Bodleian Library Ms. Gr. Th. g 11 | Oxford | UK |

| X | 1224 | 300 | Unknown gospel | Bodleian Library Ms. Gr. Th. e 8 (P) | Oxford | UK |

- Four exact dates are marked in bold type:

- three libelli are dated: all to the year 250, two to the month, and one to the day;

- a warrant to arrest a Christian is dated to 28 February 256.

| Vol | Oxy | Date | Content | Institution | City, State | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Biblical quotes | ||||||

| VIII | 1077 | 550 | Amulet: magic text quotes Matthew 4:23–24 | Trexler Library; Pap. Theol. 2 Muhlenberg College | Allentown Pennsylvania | U.S. |

| LX | 4010 | 350 | "Our Father" (Matthew 6:9ff) with introductory prayer | Papyrology Room Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

Creeds | ||||||

| XVII | 2067 | 450 | Nicene Creed (325) | Papyrology Room Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XV | 1784 | 450 | Constantinopolitan Creed (4th-century) | Ambrose Swasey Library Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School | Rochester New York | U.S. |

Church Fathers | ||||||

| III | 405 | 250 | Irenaeus, Against Heresies | Cambridge University Library Add. Ms. 4413 | Cambridge | UK |

| XXXI | 2531 | 550 | Theophilus of Alexandria Peri Katanuxeos [?] | Papyrology Rooms Sackler Library | Oxford | UK |

Unknown theological works | ||||||

| XIII | 1600 | 450 | treatise on The Passion | Bodleian Library Ms. Gr. Th. d 4 (P) | Oxford | UK |

| I | 4 | 300 | theological fragment | Cambridge University Library | Cambridge | UK |

| III | 406 | 250 | theological fragment | Library; BH 88470.1 McCormick Theological Seminary | Chicago Illinois | U.S. |

Dialogues (theological discussions) | ||||||

| XVII | 2070 | 275 | anti-Jewish dialogue | Papyrology Rooms Sackler Library | Oxford | UK |

| XVII | 2071 | 550 | fragment of a dialogue | Papyrology Rooms Sackler Library | Oxford | UK |

Apologies (arguments in defence of Christianity) | ||||||

| XVII | 2072 | 250 | fragment of an apology | Papyrology Rooms Sackler Library | Oxford | UK |

Homilies (short sermons) | ||||||

| XIII | 1601 | 400 | homily about spiritual warfare | Ambrose Swasey Library Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School | Rochester New York | U.S. |

| XIII | 1602 | 400 | homily to monks (vellum) | University Library State University of Ghent | Ghent | Belgium |

| XIII | 1603 | 500 | homily about women | John Rylands University Library Inv R. 55247 | Manchester | UK |

| XV | 1785 | 450 | collection of homilies [?] | Payrology Room Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XVII | 2073 | 375 | fragment of a homily and other text | Papyrology Rooms Sackler Library | Oxford | UK |

Liturgical texts (protocols for Christian meetings) | ||||||

| XVII | 2068 | 350 | liturgical [?] fragments | Papyrology Rooms Sackler Library | Oxford | UK |

| III | 407 | 300 | Christian prayer | Department of Manuscripts British Museum | London | UK |

| XV | 1786 | 275 | Christian hymn with musical notation | Papyrology Rooms Sackler Library | Oxford | UK |

Hagiographies (biographies of saints) | ||||||

| L | 3529 | 350 | martyrdom of Dioscorus | Payrology Room Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

Libelli (certificates of pagan sacrifice) | ||||||

| LVIII | 3929 | 250 | libellus from between 25 June and 24 July 250 | Payrology Room Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| IV | 658 | 250 | libellus from the year 250 | Beinecke Library Yale University | New Haven Connecticut | U.S. |

| XII | 1464 | 250 | libellus 27 June 250 | Department of Manuscripts British Museum | London | UK |

| XLI | 2990 | 250 | libellus from the 3rd century | Papyrology Rooms Sackler Library | Oxford | UK |

Other documentary texts | ||||||

| XLII | 3035 | 256 | warrant to arrest a Christian 28 February 256 | Payrology Room Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

Other fragments | ||||||

| I | 5 | 300 | early Christian fragment | Bodleian Library Ms. Gr. Th. f 9 (P) | Oxford | UK |

See also

- List of early Christian texts of disputed authorship

- List of early Christian writers

- List of Egyptian papyri by date

- List of New Testament minuscules

- List of New Testament papyri

- List of New Testament uncials

- Novum Testamentum Graece

- Palaeography

- Papyrology

- Tanakh at Qumran

- Textual criticism

- The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus

- Zooniverse - Ancient Lives

- Serapeum of Alexandria

References

^ Professor Nickolaos Gonis from University College London, in a film from the British Arts and Humanities Research Council on Oxyrhynchus Papyri Project.

^ World Archaeology Issue 36, 7 July 2009

^ Search by table of contents; "Oxyrhynchus Online Image Database". Imaging Papyri Project. Retrieved 25 May 2007. A listing of what each fragment contains.

^ Jarus, Owen. Live Science. 16 April 2014.

^ Sharpe, Emily. Armchair archaeologists reveal details of life in ancient Egypt. The Art Newspaper. 29 February 2016.

^ Rathbone, Dominic. Documentary of an event organised by the Hellenic Society in association with the Roman Society and the Egypt Exploration Society. 28 April 2012.

^ Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt (1898). "The Oxyrhynchus papyri". p. 187. CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

^ F. Blass, in Hermes 15 (1880:366-82); the text was identified as Aristotle's Athenaion Politeia by T. Bergk in 1881.

^ Peter John Rhodes. A Commentary on the Aristotelian Athenaion Politeia (Oxford University Press), 1981, 1993: introduction, pp. 2–5.

^ J. Mitchell and M. Caspari (eds.), p. xxvii, A History of Greece: From the Time of Solon to 403 B.C.", George Grote, Routledge 2001.

^ Rhodes, 1981, pp. 29–30.

^ e.g. Goligher, W. A. (1908). "The New Greek Historical Fragment Attributed to Theopompus or Cratippus". English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 23 (90): 277–283. doi:10.1093/ehr/xxiii.xc.277. JSTOR 550009.

^ Harding, Philipp (1987). "The Authorship of the Hellenika Oxyrhynchia". The Ancient History Bulletin. 1: 101–104. ISSN 0835-3638.

^ Meister, Klaus (2003). "Oxyrhynchus, the historian from". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth Antony (ed.). Oxford Classical Dictionary. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866172-X. CS1 maint: Extra text: editors list (link)

^ Westlake, H. D. (1960). "Review of Hellenica Oxyrhynchia by Vittorio Bartoletti". The Classical Review, New Series. Cambridge University Press. 10 (3): 209–210. doi:10.1017/s0009840x00165448. JSTOR 706964.

^ ab Bill Casselman. "One of the Oldest Extant Diagrams from Euclid". University of British Columbia. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

^ Thomas Little Heath (1921). "A history of Greek mathematics".

^ West, M. L. (1994). Ancient Greek Music. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press at the Oxford University Press. p. 281. ISBN 978-0198149750. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

^ Sophocles' Ichneutae was adapted, in 1988, into a play entitled The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus, by British poet and author Tony Harrison, featuring Grenfell and Hunt as main characters.

^ Eberhard Nestle, Erwin Nestle, Barbara Aland and Kurt Aland (eds), Novum Testamentum Graece, 27th edition, (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2001).

^ Philip W Comfort and David P Barrett. The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts. Wheaton, Illinois: Tyndale House Publishers Incorporated, 2001.

^ Kirby, Peter. "Gospel of Thomas" (2001-2006) earlychristianwritings.com Retrieved June 30, 2007.

^ Barbantani, Silvia. "Review: Gonis (N.), Obbink (D.) [et al.] (edd., trans.) The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. Volume LXIX. (Graeco-Roman Memoirs 89.)" (2007) The Classical Review, 57:1 p.66 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S0009840X06003209

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oxyrhynchus papyri. |

The Oxyrhynchus papyri (1898 publication by S.H. Hunt)- Oxford University: Oxyrhynchus Papyri Project

- Oxyrhynchus Online

Table of Contents. The Oxyrhynchus Papyri.

Trismegistos.org Online database of ancient manuscripts.- GPBC: Gazetteer of Papyri in British Collections

- The Duke Databank of Documentary Papyri. P. Oxy.: The Oxyrhynchus Papyri.

- Wieland Willker Complete List of Greek NT Papyri

- The papyri on line

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. I, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. II, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. III, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. III, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection. Digitized by Cornell University Library Digital Collections

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. IV, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. V, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. VI, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. VII, edited with translations and notes by Arthur S. Hunt, at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. VIII, edited with translations and notes by Arthur S. Hunt, at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. IX, edited with translations and notes by Arthur S. Hunt, at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. X, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection. Digitized by Cornell University Library Digital Collections ISBN 978-1-4297-3971-9

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. X, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. XI, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. XII, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. XIII, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. XIV, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. XV, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt at the Internet Archive

The Oxyrhynchus papyri vol. I - XV (single indexed PDF file)

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP