STS-48

STS-48

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

The UARS satellite in Discovery's payload bay | |

| Mission type | Satellite deployment |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1991-063A |

| SATCAT no. | 21700 |

| Mission duration | 5 days, 8 hours, 27 minutes, 38 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 3,530,369 kilometers (2,193,670 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 81 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Discovery |

| Launch mass | 240,062 pounds (108,890 kg) |

| Landing mass | 87,321 kilograms (192,510 lb)[citation needed] |

| Payload mass | 7,865 kilograms (17,339 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 5 |

| Members | John O. Creighton Kenneth S. Reightler, Jr. Charles D. Gemar James F. Buchli Mark N. Brown |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 12 September 1991, 23:11:04 (1991-09-12UTC23:11:04Z) UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 18 September 1991, 07:38:42 (1991-09-18UTC07:38:43Z) UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards Runway 22 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee | 575 kilometres (357 mi) |

| Apogee | 580 kilometres (360 mi) |

| Inclination | 57.0 degrees |

| Period | 96.2 minutes |

Left to right - Front row: Brown, Creighton, Reightler; Back row; Gemar, Buchli Space Shuttle program | |

STS-48 was a Space Shuttle mission that launched on 12 September 1991, from Kennedy Space Center, Florida. The orbiter was Space Shuttle Discovery. The primary payload was the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite. The mission landed on 18 September at 12:38 am at Edwards Air Force Base on runway 22. The mission was completed in 81 revolutions of the Earth and traveled 2.2 million miles. The 5 astronauts carried out a number of experiments and deployed several satellites. The total launch mass was 240,062 pounds (108,890 kg) and the landing mass was 192,780 pounds (87,440 kg).[citation needed]

Contents

1 Crew

1.1 Crew seating arrangements

2 Mission highlights

3 Ice particles

4 Wake-up Calls

5 See also

6 Notes

7 External links

Crew[edit]

Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | John O. Creighton Third and last spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Kenneth S. Reightler, Jr. First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Charles D. Gemar Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | James F. Buchli Fourth and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Mark N. Brown Second and last spaceflight | |

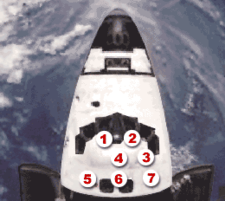

Crew seating arrangements[edit]

| Seat[1] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Creighton | Creighton | |

| S2 | Reightler | Reightler | |

| S3 | Gemar | Brown | |

| S4 | Buchli | Buchli | |

| S5 | Brown | Gemar |

Mission highlights[edit]

Liftoff of STS-48.

UARS on the remote manipulator prior to deployment.

Space Shuttle Discovery was launched into a 57-degree inclination orbit from the

Kennedy Space Center (KSC) Launch Complex 39A at 7:11 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time

(EDT) on 12 September 1991. Launch was delayed for 14 minutes at the T-5 minute

mark due to a noise problem in the air-to-ground link. The noise cleared itself, and the

countdown proceeded normally to launch.[2]

On the third day of the mission, the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS) was deployed from Discovery's payload bay 350 statute miles above Earth to study human effects on the planet's atmosphere and its shielding ozone layer. The UARS mission objectives were to provide an increased understanding of the energy input into the upper atmosphere, global photochemistry of the upper atmosphere, dynamics of the upper atmosphere, the coupling among these processes, and the coupling between the upper and lower atmosphere. This provided data for a coordinated study of the structure, chemistry, energy balance, and physical action of the Earth's middle atmosphere - that

slice of air between 10 and 60 miles above the Earth. The UARS was the first major flight element of NASA's Mission to Planet Earth, a multi-year global research program that would use ground-based, airborne, and space-based instruments to study the Earth as a complete environmental system.[3] UARS had ten sensing and measuring devices: Cryogenic Limb Array Etalon Spectrometer (CLAES); Improved Stratospheric and Mesospheric Sounder (ISAMS); Microwave Limb Sounder (MLS); Halogen Occultation Experiment (HALOE); High Resolution Doppler Imager (HRDI); Wind Imaging Interferometer (WlNDII); Solar Ultraviolet Spectral Irradiance Monitor (SUSIM); Solar/Stellar Irradiance Comparison Experiment (SOLSTICE); Particle Environment Monitor (PEM) and Active Cavity Radiometer Irradiance Monitor (ACRIM II). UARS's initial 18-month mission was extended several times – it was finally retired after 14 years of service.

Secondary payloads were: Ascent Particle Monitor (APM); Middeck 0-Gravity Dynamics Experiment (MODE); Shuttle Activation Monitor (SAM); Cosmic Ray Effects and Activation Monitor (CREAM); Physiological and Anatomical Rodent Experiment (PARE); Protein Crystal Growth II-2 (PCG II-2); Investigations into Polymer Membrane Processing (IPMP); and the Air Force Maui Optical Site (AMOS) experiment.[4]

The flight was the first to test an electronic still camera in space, a modified Nikon F4. Images obtained during the flight were monochrome with 8 bits of digital information per pixel (256 gray levels) and stored on a removable hard disk. The images could be viewed and enhanced on board using a modified lap-top computer before being transmitted to the ground via the orbiter digital downlinks.[5]

STS-48 was the second post-Challenger mission to have Kennedy Space Center as the planned

End-Of-Mission landing site, and the first mission to have a planned night landing at KSC. However, due to weather conditions at KSC in Florida, Discovery flew one extra orbit and landed at Edwards Air Force Base, California, at 3:38 a.m. EDT on 18 September 1991. The orbiter returned to KSC on 26 September 1991.[6]

Ice particles[edit]

Video while in orbit on 15 September 1991 shows a flash of light and several objects that appear to be flying in an artificial or controlled fashion. NASA explained the objects as ice particles reacting to engine jets.[7][8][9]Philip C. Plait discussed the issue in his book Bad Astronomy, agreeing with NASA.[10] This topic was also discussed in an episode of UFO Hunters.

Wake-up Calls[edit]

NASA began its longstanding tradition of waking up astronauts with music during Apollo 15. Each track is specially chosen, often by the astronauts' families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.

| Day | Song | Artist/Composer | Played For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | Hound Dog | Elvis Presley | |

| Day 3 | Release Me | Elvis Presley | In anticipation of the release of the UARS |

| Day 4 | Bare Necessities from the Jungle Book | Ken Reightler, chosen by his daughters (who were in the control room) | |

| Day 5 | Are you Lonesome Tonight | Elvis Presley | Chosen for its line “Are you sorry we drifted apart?” referring to Discovery’s separation from its payload (UARS) |

| Day 6 | Return to Sender | Elvis Presley | In anticipation of their landing that day |

See also[edit]

- List of human spaceflights

- List of Space Shuttle missions

- Nikon NASA F4

- Outline of space science

Notes[edit]

^ "STS-48". spacefacts.de. Spacefacts. Retrieved 26 February 2014..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Clatterbuck, Guy E.; Hill, William C. (1991), Mission Safety Evaluation Report for STS-48, p. 15.

^ Clatterbuck & Hill 1991, p. 28.

^ STS-48 Press Kit, NASA, September 1991.

^ Press Kit 1991, p. 25.

^ Fricke, Robert W. (1991), STS-48 Mission Report, p. 16.

^ Carlotto, Mark J. (Summer 2005). "Anomalous phenomena in space shuttle mission STS-80 video" (PDF). New Frontiers in Science. 4 (4): 17–8.

^ Fleming, Lan (Winter 2003). "A new look at the evidence supporting a prosaic explanation of the STS-48 "UFO" video" (PDF). New Frontiers in Science. 2 (2). ISSN 1537-3169.

^ Fleming, Lan (Fall 2003). "Examination of object trajectories in the STS-48 "UFO" video" (PDF). New Frontiers in Science. 3 (1). ISSN 1537-3169.

^ Plait, Philip C. (2002). Bad Astronomy. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 208–9. ISBN 0471409766.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to STS-48. |

- NASA mission summary

- STS-48 Video Highlights

Categories:

- Space Shuttle missions

- Edwards Air Force Base

- Spacecraft launched in 1991

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function()mw.config.set("wgPageParseReport":"limitreport":"cputime":"0.600","walltime":"0.795","ppvisitednodes":"value":3198,"limit":1000000,"ppgeneratednodes":"value":0,"limit":1500000,"postexpandincludesize":"value":113252,"limit":2097152,"templateargumentsize":"value":7092,"limit":2097152,"expansiondepth":"value":24,"limit":40,"expensivefunctioncount":"value":6,"limit":500,"unstrip-depth":"value":1,"limit":20,"unstrip-size":"value":20981,"limit":5000000,"entityaccesscount":"value":2,"limit":400,"timingprofile":["100.00% 629.652 1 -total"," 55.72% 350.816 7 Template:Infobox"," 40.18% 253.021 1 Template:Infobox_spaceflight"," 26.02% 163.850 1 Template:Reflist"," 13.49% 84.926 1 Template:Cite_web"," 9.97% 62.805 2 Template:Citation_needed"," 9.63% 60.615 1 Template:Commons_category"," 9.30% 58.542 2 Template:Fix"," 6.89% 43.411 4 Template:Navbox"," 6.42% 40.431 8 Template:Convert"],"scribunto":"limitreport-timeusage":"value":"0.266","limit":"10.000","limitreport-memusage":"value":7620554,"limit":52428800,"cachereport":"origin":"mw1327","timestamp":"20181211031452","ttl":1900800,"transientcontent":false););"@context":"https://schema.org","@type":"Article","name":"STS-48","url":"https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/STS-48","sameAs":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q845723","mainEntity":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q845723","author":"@type":"Organization","name":"Contributors to Wikimedia projects","publisher":"@type":"Organization","name":"Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.","logo":"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://www.wikimedia.org/static/images/wmf-hor-googpub.png","datePublished":"2004-03-02T17:30:54Z","dateModified":"2018-10-29T21:18:12Z","image":"https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/25/Sts_48_d13_uars_in_payload_bay2.jpg","headline":"human spaceflight"(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function()mw.config.set("wgBackendResponseTime":100,"wgHostname":"mw1324"););